Παρνασσός 59 (2023), εκδ. Ηρόδοτος, σελ. 397-431

Περίληψη

Περίληψη

Τα σημεία τριβής στις σχέσεις κράτους και ορθοδόξου Εκκλησίας είναι ορατά από τη σύσταση του νεοελληνικού κράτους. Τα προβλήματα που ανέκυπταν κάθε τόσο αφορούσαν σε διαφορετικά θέματα. Ο αντίκτυπος του προβλήματος της αντιπαράθεσης άγγιξε και το εκπαιδευτικό σύστημα της χώρας με το γλωσσικό να βρίσκεται πάντοτε στην πρώτη γραμμή ολόκληρο τον 19ο αιώνα και το μεγαλύτερο μέρος του εικοστού. Η χρονική περίοδος 1900-1946 αμαυρώθηκε με τις αλλεπάλληλες αντιθέσεις γύρω από το γλωσσικό ζήτημα, με τους δύο αρχαιότερους θεσμούς να κορυφώνουν την αντιπαράθεσή τους κατά το διάστημα 1900-1946.

To γλωσσικό ζήτημα υπήρξε πεδίο αντιπαραθέσεων και συγκρούσεων από την ίδρυση του βασιλείου της Ελλάδος και συνδέεται αναπόσπαστα με την πορεία του εκπαιδευτικού συστήματος της χώρας. Το τρίσημο σχήμα του ιστορικού Κωνσταντίνου Παπαρρηγόπουλου (αρχαιότης – Βυζάντιο – νέος ελληνισμός) είναι ο οδοδείκτης της αδιαμφισβήτητης συνέχειας του ελληνικού έθνους και το συστατικό στοιχείο της εθνικής ιδεολογίας. Στο σχήμα αυτό η γλώσσα καταλαμβάνει μαζί με τη θρησκεία μια δεσπόζουσα θέση. Ο ίδιος δεν ασχολήθηκε ιδιαίτερα με το θέμα της γλώσσας, χωρίς να αποκρύπτει τον θαυμασμό του για την καταπληκτική ομοιότητα της αρχαίας ελληνικής γλώσσας με την καθομιλουμένη στην αναγεννημένη καινούργια Ελλάδα. Για τον Σπυρίδωνα Ζαμπέλιο, συνοδοιπόρο του Κ. Παπαρρηγόπουλου, στην αναστήλωση του Βυζαντίου η απόδειξη συνέχειας και αδιάσπαστης ενότητας είναι η γλώσσα, «το μόνον λείψανον της ναυαγησάσης αρχαιότητος». Η εξέλιξη της αρχαίας ελληνικής γλώσσας ήταν το αναγκαίο κακό που ο λαός αναλαμβάνει με τους ακατάπαυστους σολοικισμούς του να διαφυλάξει με έναν δικό του τρόπο, μέσα από τον οποίο υφίσταται η εθνική του συνείδηση. Έτσι, με τη χρήση της καθαρεύουσας οι Έλληνες οδηγούνται ξανά στην γνώση και χρήση της αρχαίας Ελληνικής γλώσσας. Η επίσημη χρήση της καθαρεύουσας στον κρατικό μηχανισμό υιοθετήθηκε, ώστε να μοιάζει το νεοσύστατο κράτος με ένα ευρωπαϊκό. Οι λόγιοι άνδρες την θεωρούσαν απαραίτητο δρόμο που έπρεπε ο λαός να ακολουθήσει όπως ενήργησε η επίσημη πολιτεία, το πανεπιστήμιο και η Εκκλησία στην Ελλάδα, σε αντίθεση με την πορεία των υπόλοιπων εθνών-κρατών στη Βαλκανική Χερσόνησο, που προσαρμόζουν τη καθομιλουμένη γλώσσα τους στις δυτικές επιταγές προσαρμοζόμενες στις επιστημονικές εξελίξεις του ευρωπαϊκού χώρου (1).

Στο τέλος του 18ου αιώνα οι ιδέες του ευρωπαϊκού Διαφωτισμού είχαν κερδίσει έδαφος και στους Έλληνες εντός των ορίων της Οθωμανικής κυριαρχίας. Εκείνη την περίοδο διαμορφώνονται δύο διαφορετικά στρατόπεδα που το ένα εκπροσωπούσε συντηρητικούς κύκλους οι οποίοι υπερασπίζονταν την αρχαία Ελληνική γλώσσα, ενώ στην αντίπερα όχθη βρίσκονταν οι λόγιοι που αναζητούσαν – με γνώμονα τις ιδέες του Διαφωτισμού – για τον ίδιο λόγο την διαμόρφωση μιας κοινής γλώσσας για όλους τους υπόδουλους Έλληνες. Στο μέσον αυτής της διαμάχης δηλαδή, στους αρχαϊστές και δημοτικιστές, ο ηγέτης των οπαδών του ελληνικού Διαφωτισμού, Αδαμάντιος Κοραής, προτρέπει τους Έλληνες να επιλέξουν όπως ο ίδιος προηγουμένως είχε προτείνει τη «μέση οδό». Ο Α. Σατραζάνης γράφει: «[…]δεν ήταν τίποτα άλλο ουσιαστικά, από μια εκλεπτυσμένη και εμπλουτισμένη από λόγιες λέξεις της εποχής του γλώσσας, βασισμένης, ωστόσο, στα πρότυπα της αρχαίας. Με την ενέργειά του αυτή κατέστη ο πρώτος διαμορφωτής της “καθαρεύουσας γλώσσας” στην οποία κυριαρχούσε η λογική, αλλά κυρίως ο ορθολογικός ρεαλισμός του ιδίου του δημιουργού της». Οι μόνοι που δεν ακολουθούν από τους λογοτεχνικούς κύκλους την επιλογή του πατέρα του Ελληνικού Διαφωτισμού Αδ. Κοραή είναι οι λογοτέχνες των Ιονίων νήσων, με αντιπάλους τους Φαναριώτες που δεν χάνουν καμία ευκαιρία για να εκφράσουν την αποστροφή τους. Το έτος 1813 ο Φαναριώτης Ιακωβάκης Ρίζος Νερουλός στην κωμωδία του υπό τον τίτλο «Κορακίστικα», στρέφεται ανοικτά κατά των διαφόρων διαλέκτων του ελληνόφωνου κόσμου αλλά και του Αδαμάντιου Κοραή. Όμως οι φοβίες όλων αυτών των διανοούμενων του ελληνόφωνου κόσμου αντικατοπτρίζουν τις πολλές αμφιβολίες και ανησυχίες των εθνικιστικών ομάδων. Το ελληνικό νεοσύστατο κράτος ήθελε να υπάρχει ένα μοναδικό γλωσσικό όργανο για να λυθεί το πρόβλημα με τις τοπικές διαλέκτους (2).

Η διαμόρφωση εθνικής συνείδησης για την οικοδόμηση του νεοσύστατου κράτους ήταν στις άμεσες προτεραιότητες ώστε η Ελλάδα να γίνει ένα σύγχρονο ευρωπαϊκό κράτος ισότιμο με τα υπόλοιπα της γηραιάς ηπείρου. Η δημιουργία ενός έθνους έπρεπε να υπερβεί επειγόντως τις εσωτερικές αντιθέσεις και αντιδράσεις που κληρονομήθηκαν από το παρελθόν. Τα δύο μεγαλύτερα προβλήματα αφορούσαν στην απροθυμία να πειθαρχήσουν στους νέους θεσμούς όλοι όσοι έλαβαν μέρος στην Επανάσταση του 1821 και η πολυγλωσσία που κυριαρχούσε. Η ενσωμάτωσή τους έγινε μέσα από την ένταξή τους στον τακτικό ελληνικό στρατό. Το τοπικιστικό πνεύμα στη διάρκεια του αγώνα του 1821 έγινε αφορμή για μια σειρά εμφυλίων πολέμων και ο Ιωάννης Καποδίστριας κατέστη στόχος που το πλήρωσε με τη ζωή του. Στο ίδιο κλίμα κινήθηκαν και οι Βαυαροί στην Ελλάδα, προσπαθώντας με τη συγκρότηση τακτικού στρατού να ελέγξουν το ζήτημα. Ο στρατός συνετέλεσε με πολλούς τρόπους στην κοινωνική ομοιογένεια. Ένας από αυτούς ήταν η υποχρεωτική χρήση από τους στρατιώτες της ελληνικής γλώσσας και ιδίως όσων δεν την είχαν ως μητρική γλώσσα. Ο Δ.Κ. Βυζάντιος το έτος 1840 στο έργο του υπό τον τίτλο «Η Βαβυλωνία ή η κατά τόπους διαφθορά της ελληνικής γλώσσης. Κωμωδία εις πράξεις πέντε», περιγράφει με εύγλωττο τρόπο τις διάφορες αλλοιώσεις που η ελληνική γλώσσα είχε υποστεί συνδυαζόμενη με τις ξενόφερτες λέξεις που είχαν ενταχθεί στο λεξιλόγιο των νεοελλήνων. Μέσα σε αυτό το κλίμα που είχε διαμορφωθεί το νεότευκτο Οθώνειο Πανεπιστήμιο αναλαμβάνει να επιλύσει αυτό το μεγάλο πρόβλημα. Στις πρώτες δεκαετίες του 20ου αιώνα ένα νέο πανεπιστήμιο στη χώρα, το Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης, καθίσταται πόλος έλξης των δημοτικιστών (3).

Το γλωσσικό ζήτημα υπήρξε πεδίο αντιπαραθέσεων και συγκρούσεων από τη σύσταση του νεοελληνικού κράτους έως την καθιέρωση της δημοτικής, με αιχμή του δόρατος τη χρήση της στον χώρο της εκπαίδευσης και στα διδακτικά εγχειρίδια. Η διαμάχη γύρω από το γλωσσικό ζήτημα κορυφώθηκε με την κυκλοφορία του έργου του Γιάννη Ψυχάρη υπό τον τίτλο «Το ταξίδι μου». Ο συγγραφέας ουσιαστικά άνοιγε το δρόμο για τη συγγραφή περισσοτέρων βιβλίων στη δημοτική γλώσσα, σπάζοντας την παράδοση, αφού γλώσσα και πατρίδα ήταν το ίδιο για εκείνον όπως έγραφε η έκδοση το έτος 1888 του βιβλίου του, που υπήρξε η αφετηρία ενός πολύχρονου αγώνα για την επικράτηση στα εκπαιδευτικά πράγματα και την υιοθέτηση από το ελληνικό κράτος της δημοτικής, με το αρχαϊστικό πνεύμα να αμφισβητείται δημόσια όλο και περισσότερο. Η χρήση της δημοτικής στον χώρο της λογοτεχνίας αποτελεί την αφετηρία για τον εξοστρακισμό της καθαρεύουσας που θα κρατήσει περίπου έναν αιώνα (4).

Η εξέλιξη του γλωσσικού ζητήματος συνδέθηκε από πάρα πολλούς στην Ελλάδα με το κίνημα του πανσλαβισμού. Η επιρροή των τριών προστάτιδων Δυνάμεων παρέμεινε υπολογίσιμη για το μικρό βασίλειο ακόμα και με την έλευση στην Ελλάδα της νέας δυναστείας. Το 1856 μετά τον Κριμαϊκό πόλεμο η εξωτερική πολιτική της τσαρικής Ρωσίας αλλάζει πορεία, αφού από προστάτιδα δύναμη των ορθοδόξων λαών μέσα στα όρια της Οθωμανικής αυτοκρατορίας καταλήγει να υπερασπίζεται σε κάθε αφορμή τους Σλάβους, τονίζοντας τον ιδιαίτερο ρόλο που έπρεπε να αναλάβουν να διαδραματίσουν οι Σλάβοι κάτω από το άγρυπνο βλέμμα της τσαρικής Ρωσίας ανάμεσα στους ορθοδόξους λαούς. Η Ρωσία ουσιαστικά χρησιμοποιεί τους Σλάβους για να εφαρμόσει τα σχέδιά της στη Βαλκανική Χερσόνησο με εύκολο τρόπο. Οι μεσσιανικές αντιλήψεις για τον ρόλο όλων των Σλάβων με αρχηγό την τσαρική Ρωσία στα όρια της Οθωμανικής αυτοκρατορίας αξιοποιήθηκαν κατάλληλα από τους Βούλγαρους. Ο πρεσβευτής τη Ρωσίας Ιγνάτιεφ στην Υψηλή Πύλη ανήκε και αυτός στους οπαδούς αυτής της τάσης. Οι Βούλγαροι επομένως ανακαλύπτουν έναν μεγάλο σύμμαχο για να υλοποιήσουν τα σχέδιά τους. Ο Ιγνάτιεφ αξιολογεί την κατάσταση και, αξιοποιώντας τις ανησυχίες των Οθωμανών για τις δραστηριότητες των ρωμαιοκαθολικών Γάλλων ιεραποστόλων που προσπαθούσαν να εντάξουν τους Βουλγάρους στους Ουνίτες, αναλαμβάνει δράση. Έτσι, ο σουλτάνος αντιλαμβανόμενος την δυσκολία της κατάστασης που είχε αρχίσει να διαμορφώνεται, ταυτίζεται με τα συμφέροντα της Ρωσίας που διαπίστωνε ότι εξασθενούσε η δύναμή της στην περιοχή του Αίμου όπου κυριαρχούσαν οι Βούλγαροι. Ως εκ τούτου, πιέζει και επιτυγχάνει την αυτονομία της Ορθόδοξης Εκκλησίας των Βουλγάρων με το όνομα Εξαρχία, το έτος 1870. Ο πατριάρχης Κωνσταντινουπόλεως Γρηγόριος ΣΤ’ το έτος 1869 υπέβαλε στην Υψηλή Πύλη σχέδιο αναγνώρισης της Βουλγαρικής Εκκλησίας. Όμως, οι σκληροπυρηνικοί Βούλγαροι το απέρριψαν, διότι δεν περιελάμβανε όλες τις περιοχές που επιθυμούσαν. Με φιρμάνι του σουλτάνου αναγνωρίζεται το 1870 η αυτοκέφαλη Βουλγαρική Εξαρχία, ενώ προβλεπόταν σε αυτό η Βουλγαρική Εξαρχία να υπερισχύει όπου τα 2/3 των κατοίκων μιας περιοχής δήλωναν ότι ήταν Βούλγαροι. Το Οικουμενικό Πατριαρχείο Κωνσταντινουπόλεως το 1872 καταδίκασε το φαινόμενο του Εθνοφυλετισμού κηρύσσοντας ουσιαστικά τους Βούλγαρους σχισματικούς. Με τη Συνθήκη του Βερολίνου το 1878 όλοι οι λαοί της Βαλκανικής Χερσονήσου αρχίζουν τον αγώνα για να δικαιωθούν από την ιστορία με την επιτυχία των εθνικών τους οραματισμών. Στα σχέδιά τους περιλαμβανόταν η Μακεδονία που η πληθυσμιακή σύνθεση της περιοχής εκείνης την εποχή μεγαλώνει τον ανταγωνισμό. Όσοι άνθρωποι μιλούσαν κάποιο σλαβικό ιδίωμα έγιναν στόχος για τους Βούλγαρους ως απόδειξη της διαφοροποίησής τους (5).

Οι εξεγέρσεις το καλοκαίρι του 1875 στο βόρειο μέρος της Βαλκανικής Χερσονήσου μεταβάλλει ριζικά τα σχέδια όλων των εμπλεκομένων. Ο πανσλαβισμός στην τσαρική Ρωσία ήταν πλέον πανίσχυρος, με αποτέλεσμα να αντιμετωπίζει την Ελλάδα με έναν τελείως διαφορετικό τρόπο, αλλάζοντας την πολιτική που ακολουθούσε μέχρι τότε, παραχωρώντας με ευκολία την εγκαταλελειμμένη μικρή Ελλάδα στην επιρροή των Άγγλων. Η δεκαετία του 1870 ήταν η δυσκολότερη για το μικρό βασίλειο σε όλο τον 19ο αιώνα. Το πολιτικό σκηνικό της χώρας πνιγόταν στα σκάνδαλα. Η όγδοη και τελευταία κυβέρνηση του Δημητρίου Βούλγαρη καταρρέει υπό το βάρος δύο τεραστίων διαστάσεων σκανδάλων. Το ένα αφορούσε στα πολιτικά πράγματα και έμεινε στην ιστορία γνωστό ως «στηλιτικά» και το άλλο τα εκκλησιαστικά που έμεινε γνωστό στην ιστορία ως «σιμωνιακά». Η διαπάλη και η διαπλοκή της πολιτικής με την εκκλησιαστική εξουσία είχε αποδείξει στην πράξη ποια ήταν τα νοσηρά αποτελέσματα της πολιτειοκρατίας που είχε επιβληθεί στην Ελλάδα από την περίοδο της βαυαροκρατίας. Το 1874 το ελληνικό κράτος οδηγούνταν σε εμφύλια σύρραξη με αποδεδειγμένη νοθεία του εκλογικού αποτελέσματος της κυβέρνησης Δ. Βούλγαρη, με την πολιτική κρίση να τελειώνει δύο μήνες πριν αρχίσει η αντίστοιχη βοσνιακή κρίση (6).

Το έτος 1804 ιδρύθηκε η Βρεταννική Βιβλική Εταιρία με στόχο τη μετάφραση της Βίβλου σε όλες τις ομιλούμενες γλώσσες του πλανήτη, σε μια εποχή που η δραστηριοποίηση των διαμαρτυρομένων μισσιονάριων ήταν αυξημένη. Η επιθυμία τους για την άμεση διείσδυσή τους στην Ανατολή με σκοπό τον επανευαγγελισμό των ορθοδόξων έγινε με αιχμή του δόρατος αυτήν την φορά τη μετάφραση της Βίβλου στην καθομιλουμένη γλώσσα. Το έτος 1810 μια καινούργια δίγλωσση έκδοση, που είχε δει για πρώτη φορά το 1710 το φως της δημοσιότητας στο Halle της Σαξονίας, με έξοδα της βασίλισσας της Πρωσίας από τον Ναουσαίο Αναστάσιο Μιχαήλ με αναθεωρημένο το κείμενο του Σεραφείμ Μυτιληναίου, κυκλοφόρησε το 1814 με άδεια του πατριάρχη Κυρίλλου ΣΤ’ (1813-1818). Το 1827 κυκλοφόρησε μια άλλη ανώνυμη αναθεώρηση όπως και το 1830. Στην προσπάθεια αυτή συνετέλεσε ο Αδαμάντιος Κοραής, που με επιστολή του το 1808 στη Βρετανική Βιβλική Εταιρία εξέφραζε το ενδιαφέρον του για τη μετάφραση της Βίβλου, αλλά και τη δική του πρωτοβουλία να μεταφράσει μια από τις ποιμαντικές επιστολές του αποστόλου Παύλου, την Προς Τίτον επιστολή. Το έτος 1818, ο ποιμένας Charles Williamson ήρθε σε επαφή με τον Σιναΐτη κληρικό Ιλαρίωνα, λόγιο με μεγάλη μόρφωση, για μια νέα μετάφραση με την ευλογία των πατριαρχών Κυρίλλου Στ’ και Γρηγορίου Ε’. Το έτος 1820 του ανατέθηκε η μετάφραση της Παλαιάς Διαθήκης. Η αντίδραση του Κωνσταντίνου Οικονόμου του εξ Οικονόμων ήταν σφοδρή σε Κωνσταντινούπολη και Ρωσία παρά τις αρχικές θετικές του δηλώσεις. Η κήρυξη της Επαναστάσεως του 1821 ματαίωσε την συγκεκριμένη έκδοση. Η Βρετανική Βιβλική Εταιρεία απέρριψε την ιδέα της μετάφρασης της Παλαιάς Διαθήκης από το κείμενο των Ο’, προτιμούσε να χρησιμοποιηθεί το εβραϊκό πρωτότυπο κείμενο για αυτόν τον σκοπό. Η μετάφραση της Καινής Διαθήκης εκδόθηκε σε δύο εκδόσεις, μία μαζί με το πρωτότυπο και η άλλη χωρίς αυτό, το έτος 1828. Η πρώτη έκδοσή του ξανατυπώθηκε το έτος 1831 στη Γενεύη και αντίτυπα διανεμήθηκαν στην Ελλάδα από τον Ι. Καποδίστρια. Η δραστηριοποίηση στις περιοχές όλων των ορθόδοξων πατριαρχείων της Βρετανικής Βιβλικής Εταιρείας συνοδεύτηκε από έκρηξη δραστηριοτήτων των προτεσταντών ιεραποστόλων, όπως η ίδρυση σχολείων και η ευρεία κυκλοφορία βιβλίων και έντυπου υλικού σε γλώσσα που μπορούσε εύκολα να αντιληφθεί ο λαός, με αποκορύφωμα τη μετάφραση της Βίβλου σε απλή γλώσσα. Η μετάφραση του Ιλαρίωνα κυκλοφόρησε ξανά, αφού έγιναν οι απαραίτητες διορθώσεις για χρήση των μαθητών. Η Βρετανική Βιβλική Εταιρεία έλαβε την απόφαση να χρηματοδοτήσει μια νέα μετάφραση του ιερού κειμένου των χριστιανών. Σε αυτό το νέο δύσκολο εγχείρημα επιλέχθηκε ο καθηγητής στην Ιόνιο Ακαδημία της Κέρκυρας, και μετέπειτα καθηγητής της φιλοσοφίας στο Οθώνειο πανεπιστήμιο, αρχιμανδρίτης Νεόφυτος Βάμβας. Η επιλογή του Βάμβα έγινε ύστερα από υπόδειξη του Αδ. Κοραή, ο οποίος ήταν γνωστός για τα φιλικά του αισθήματα απέναντι στον προτεσταντισμό και υποστηρικτής του έργου της Εταιρείας. Ένα άλλο θετικό στοιχείο ήταν η διαμονή του Ν. Βάμβα στην Κέρκυρα που βρισκόταν κάτω από αγγλική κηδεμονία, και εμπόδιζε τις επιρροές που αυτός θα δεχόταν από το πατριαρχείο Κωνσταντινουπόλεως για το έργο το οποίο θα αναλάμβανε. Εκτός από τον Νεόφυτο Βάμβα, η Εταιρεία ανέθεσε τη μετάφραση της Παλαιάς Διαθήκης από το πρωτότυπο κείμενο στους καθηγητές της Ιονίου Ακαδημίας Κωνσταντίνο Τυπάλδο-Ιακωβάτο και Γεώργιο Ιωαννίδη. Ολόκληρη η Παλαιά Διαθήκη κυκλοφόρησε σε έναν τόμο το έτος 1840. Η Καινή Διαθήκη εκδόθηκε ολόκληρη το έτος 1844. Οι αντιδράσεις γι αυτές τις μεταφράσεις δεν άργησαν να έρθουν. Ο Κωνσταντίνος Οικονόμος ο εξ Οικονόμων στράφηκε εναντίον αυτού του εγχειρήματος. Η Βρεττανική Βιβλική Εταιρεία προέβη σε κάποιες διορθώσεις στο κείμενο της μετάφρασης. Η εφημερίδα Εθνική της Αθήνας στις 15-11-1834 δημοσίευσε επιστολή με υπογραφή «Ιωσήφ Νικοδήμου» από την Κωνσταντινούπολη. Η εντύπωση που δημιουργήθηκε στους αναγνώστες αυτής της επιστολής ήταν πως συντάκτης της υπήρξε ο πρώην οικουμενικός πατριάρχης Κωνσταντινουπόλεως Κωνστάντιος Α’. Οι προτεστάντες τη χαρακτήρισαν μια πολεμική κίνηση εναντίον τους από την ορθόδοξη ανατολική εκκλησία. Η αντίδραση πάντως ήταν καθολική αφού συνεχίστηκε και από τους πατριάρχες Κωνστάντιο Β’ και Γρηγόριο ΣΤ’. Στη συνέχεια απαγόρευσε το πατριαρχείο Κωνσταντινουπόλεως την είσοδο των ιεραποστόλων στα σχολεία και τη χρήση έντυπου υλικού και βιβλίων από τους νεαρούς μαθητές. Οι ξένες κυβερνήσεις, μέσω των διπλωματικών τους αποστολών στο νεοσύστατο κρατίδιο, πίεζαν να αμβλυνθεί η στάση της κυβερνήσεως απέναντι στις πιέσεις που ασκούσαν εκκλησιαστικοί κύκλοι στην Ελλάδα και το πέτυχαν με αποτέλεσμα τη διαίρεση του λαού (7).

Το μεγαλύτερο πρόβλημα που αντιμετώπισε η ελληνική κοινωνία στα πρώτα χρόνια του ελεύθερου βίου της ήταν η εισροή πνευματικών κινημάτων, ξένων προς την ελληνική πραγματικότητα, που δημιουργούσαν κάποια πνευματική σύγχυση στην πλειονότητα του λαού. Ένα από τα επικρατέστερα πνευματικά κινήματα ήταν και ο ρομαντισμός, που για 50 χρόνια άσκησε μεγάλη επιρροή στα πνευματικά ζητήματα του τόπου. Οι τάσεις για αξιοποίηση της αρχαιότητας και του πολιτισμού της αποτελεί όπως ο Χ. Βούλγαρης επισημαίνει: Αξιοθαύμαστον προσπάθειαν αναζητήσεως της αυτοσυνειδησίας του νεότερου ελληνισμού (8).

Έναντι αυτού του πνευματικού φαινομένου του 19ου αιώνα που εκφράστηκε από την «Αθηναϊκή Σχολή», ένα νέο πνευματικό κίνημα της γενιάς του 1880, η «Νέα Αθηναϊκή Σχολή», δημιουργεί το κατάλληλο κλίμα για την εμφάνιση στο προσκήνιο των οπαδών της δημοτικής γλώσσας. Πρωτεργάτης αυτής της ομάδας υπήρξε ο Γιάννης Ψυχάρης, με συνοδοιπόρο τον φίλο του Αλέξανδρο Πάλλη. Έκτοτε εμφανίζεται το «γλωσσικό ζήτημα», που ταλαιπώρησε για πολλές δεκαετίες την ιστορία και την πορεία του ελληνικού εκπαιδευτικού συστήματος. Μέσα σε αυτό το γενικό πλαίσιο τοποθετείται και η διάθεση για να μεταφραστεί η Καινή Διαθήκη σε απλή γλώσσα κατανοητή για τον απλό άνθρωπο, που ήθελε να έρθει σε επαφή με το ιερό κείμενο. Από τα τέλη του 19ου αιώνα, μετά τον ατυχή πόλεμο του 1897, μια καινούργια οξύτερη περίοδος αρχίζει για το ζήτημα της μεταφράσεως της Καινής Διαθήκης. Η μετάφραση της Αγίας Γραφής αντιμετωπίσθηκε με καχυποψία από τους Έλληνες. Το έτος 1834 σημειώθηκε η έναρξη του αγώνα κατά των προτεσταντών ιεραποστόλων μέσα από τις αντιδράσεις για τη μετάφραση της Βίβλου. Η ανακήρυξη του αυτοκεφάλου της Ορθόδοξης Εκκλησίας στην Ελλάδα το 1833 από τους Βαυαρούς είχε ως αποτέλεσμα οι Ορθόδοξοι να καταλήξουν σχισματικοί και να αποκοπούν πνευματικά από το Οικουμενικό Πατριαρχείο. Η εξέλιξη αυτή συνδυάσθηκε από τους Έλληνες με την σχεδόν ταυτόχρονη έκδοση μεταφρασμένων αποσπασμάτων από το κείμενο της Παλαιάς Διαθήκης (9).

Ο Σ. Γιαγκάζογλου γράφει: «Η συνήθης αρνητική αντίδραση στην εισαγωγή μεταφράσεων στη λατρεία της Εκκλησίας σχετίζεται με μια συγκεκριμένη αντίληψη της Εκκλησίας και της Θεολογίας με τον πολιτισμό. Ως πολιτισμός συνήθως αναγνωρίζεται η διαφύλαξη κορυφαίων επιτευγμάτων και αξεπέραστων ιστορικών κατακτήσεων του παρελθόντος» (10).

Στις 14 Οκτωβρίου 1890 ο Χαρίλαος Τρικούπης ηττάται στις εκλογές και αναδεικνύεται νικητής ο Θ. Δηλιγιάννης που δεν μπορεί να δώσει λύση στο μεγάλο οικονομικό αδιέξοδο του ελληνικού κράτους. Η Βουλγαρία εκείνη την περίοδο στηρίζεται στις ξένες δυνάμεις για την εσωτερική της ανασυγκρότηση, ενώ δημιουργεί τον ισχυρότερο στρατό στη Βαλκανική Χερσόνησο. Τα οικονομικά του ελληνικού κράτους χειροτερεύουν και το νόμισμα υποτιμάται. Ο βασιλιάς Γεώργιος Α’ παύει τον πρωθυπουργό από τα καθήκοντά του, ενώ αναλαμβάνει υπηρεσιακός πρωθυπουργός ο Κων. Κωνσταντόπουλος. Στις εκλογές τα ηνία της χώρας αναλαμβάνει ξανά ο Χαρίλαος Τρικούπης ο οποίος αναγκάζεται να στραφεί στο εξωτερικό για να εξασφαλίσει η χώρα νέο δάνειο. Οι προσπάθειές τους έμειναν άκαρπες. Οι Άγγλοι θέτουν ως όρο την επιβολή διεθνούς έλεγχου. Ο Χ. Τρικούπης παραιτείται, αλλά λίγους μήνες αργότερα στην Ελλάδα η αντιπολίτευση υπό τον Θ. Δηλιγιάννη κατάφερε να αναγκάσει τον Χ. Τρικούπη να διεξαγάγει εκλογές στις οποίες ηττήθηκε και αποσύρθηκε στις Κάννες της Γαλλίας όπου και πέθανε τον Μάρτιο του 1896. Η νέα κυβέρνηση Δηλιγιάννη αδυνατεί να βάλει σε τάξη τα οικονομικά της χώρας και είναι αντιμέτωπη με τον αγγλορωσικό ανταγωνισμό στην περιοχή. Η Ρωσία και η Γερμανία ποδηγετούν την οθωμανική αυτοκρατορία, με τους Άγγλους να ωθούν τους Αρμενίους να στασιάσουν, χωρίς καμία επιτυχία. Την ίδια εποχή στη νήσο Κρήτη σημειώνονται ταραχές, ενώ η Μακεδονία βιώνει μια σκληρή επίθεση από τους Βούλγαρους Κομιτατζήδες που προσπαθούν να αρπάξουν ολόκληρη την περιοχή και να την εντάξουν στο δικό τους κράτος. Η ελληνική κυβέρνηση αδυνατεί να ενεργήσει. Τότε, κάποιοι χαμηλόβαθμοι αξιωματικοί όπως και ο Κ. Πάλλης, Παύλος Μελάς, Λ. Φωτιάδης κ.α. συγκροτούν την «Εθνικήν Εταιρείαν» τον Σεπτέμβριο του 1895, με στρατιωτικούς και πολιτικούς κύκλους να συντάσσονται με τους σκοπούς της. Η Εταιρεία οργανώνει στρατιωτικά σώματα με περίπου 400 άντρες και αναμετρήθηκαν με τους κομιτατζήδες και τους Οθωμανούς που προσπαθούσαν να κρατήσουν υπό τον έλεγχό τους την περιοχή. Την ίδια περίοδο οι Έλληνες αποβιβάζονταν στην Κρήτη φέρνοντας μαζί τους πολεμικό υλικό. Οι ένοπλες συγκρούσεις ξεσπούν. Οι Έλληνες καταλαμβάνουν το Ακρωτήρι και κηρύσσουν την πολυπόθητη ένωση. Στην Αθήνα η κυβέρνηση ανίκανη να αντιμετωπίσει τις κραυγές της αντιπολίτευσης που την πιέζουν μαζί με τους αξιωματικούς και την κοινή γνώμη, στέλνει στρατό στη μεγαλόνησο με επικεφαλής τον συνταγματάρχη Τιμολέοντα Βάσο με σαφή εντολή να διώξει τον οθωμανικό στρατό. Οι ξένες δυνάμεις αντιμέτωπες με την απειλή κήρυξης νέου πολέμου υπόσχονται αυτονομία στο νησί με όρο να αποσυρθεί ο ελληνικός στρατός. Η πρόταση, των ξένων απορρίφθηκε με αποτέλεσμα να αρχίσουν οι ένοπλες συγκρούσεις. Έτσι, ο ελληνικός στρατός ήρθε αντιμέτωπος με τον πολύ καλά εξοπλισμένο και εκπαιδευμένο οθωμανικό στρατό. Η ήττα ήταν αναπόφευκτη παρά την ηρωική δράση των Ελλήνων στρατιωτών στην Ήπειρο και στη Θεσσαλία. Όλα έληξαν έναν μήνα αργότερα με τη διαμεσολάβηση των ξένων δυνάμεων. Η νέα συνθήκη ειρήνης επέβαλε ελάχιστη παραχώρηση εδάφους από την ελληνική πλευρά και καταβολή πολεμικής αποζημίωσης 4.000.000 τουρκικών λιρών και διεθνή οικονομικό έλεγχο στη χώρα (11).

Ο θρησκευτικός σύλλογος “Ανάπλασις” το έτος 1900 αναλαμβάνει τη μετάφραση του Κατά Ματθαίον Ευαγγελίου. Ο αντιπρόεδρος του συλλόγου Κ. Διαλησμάς είχε τις ανάλογες επαφές τόσο με το Οικουμενικό Πατριαρχείο Κωνσταντινουπόλεως όσο και με την Ιερά Σύνοδο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος για να χαρτογραφήσει το έδαφος, λαμβάνοντας τις ανάλογες οδηγίες για τη συγκεκριμένη προσπάθεια ώστε να στεφθεί με επιτυχία. Το ζήτημα της μεταφράσεως της Αγίας Γραφής είχε έρθει ξανά στην επικαιρότητα με την εμφάνιση των ξένων μισιονάριων λίγο πριν από το ξέσπασμα της Επαναστάσεως του 1821, δημιουργώντας επιπλοκές αφού συνδέθηκε με την προσπάθεια των προτεσταντών ιεραποστόλων να ελέγξουν με κάθε τρόπο τόσο τη δημόσια όσο και την ιδιωτική εκπαίδευση στο νεοσύστατο κρατίδιο. Ένας άλλος λόγος που ο Κ. Διαλησμάς δεν ήθελε να βρεθεί αντιμέτωπος με την Ορθόδοξη Εκκλησία εντός και εκτός συνόρων είχε τις ρίζες του στην αντιμετώπιση του κινήματος του ευσεβισμού υπό τον Απόστολο Μακράκη. Ήταν νωπές οι μνήμες των αποτελεσμάτων αυτής της σύγκρουσης και των συνεπειών της για τους οπαδούς και τον ίδιο τον λαϊκό ιεροκήρυκα Απόστολου Μακράκη (12).

Από τα τέλη του 19ου αιώνα μια οξύτερη φάση αρχίζει για το θέμα της μεταφράσεως του κειμένου της Καινής Διαθήκης. Η βασίλισσα Όλγα επισκεπτόμενη στα νοσοκομεία τους τραυματίες του ατυχούς πολέμου του 1897, αλλά και τους φυλακισμένους, θέλησε να τους προσφέρει το ιερό κείμενο σε κατανοητή για εκείνους γλώσσα. Από την εμπειρία που είχε αποκτήσει στην πατρίδα της, ο απλός λαός διάβαζε ικανοποιημένος την Καινή Διαθήκη, σε μετάφραση. Ήδη, από το 1817 στην Πετρούπολη υπήρχε μεταφρασμένο στα ελληνικά και κυκλοφορούσε το κείμενο της Καινής Διαθήκης (13).

Στην προμετωπίδα της εκδόσεώς του ο Σύλλογος “Ανάπλασις” έγραφε: «Το κατά Ματθαίον Άγιον Ευαγγέλιον εις το πρωτότυπον κείμενον, εις ερμηνείαν σύντομον και εις προσευχάς. Έκδοσις Συλλόγου “Αναπλάσεως” τη συστάσει δι’ Εγκυκλίου της Μεγάλης Εκκλησίας προς ακώλυτον κυκλοφορίαν και εν τω κλίματι του Οικουμενικού Θρόνου. Εν Αθήνας δαπάνη Μελετίου Βαγιανέλλη Αρχιμανδρίτου, 1900». Σε αυτήν την έκδοση περιλαμβάνονταν το πρωτότυπο κείμενο, η ερμηνεία του μαζί με προσευχές και ήταν έργο του Κωνσταντίνου Διαλησμά. Ο Οικουμενικός Πατριάρχης Άνθιμος Ζ’ με επιστολή του με ημερομηνία 7-12-1896 αποδεχόταν τη συγκεκριμένη προσπάθεια και παρείχε τις κατάλληλες οδηγίες τις οποίες έπρεπε να ακολουθήσουν. Το πρωτότυπο κείμενο του Ευαγγελίου έπρεπε να υπάρχει, ενώ η μετάφραση έπρεπε να χρησιμοποιεί λέξεις «[…] ας το οίκοθεν εννοείται». Ο Σύλλογος αφού έλαβε έγκριση για τις συγκεκριμένες προσευχές από την Ιερά Σύνοδο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος, για να τις προσθέσει στο κείμενο όρισε επιτροπή αποτελούμενη από πέντε μέλη του Συλλόγου με επίτιμο πρόεδρο της επιτροπής του μητροπολίτη Αθηνών Προκόπιο. Στη συνέχεια ο Σύλλογος με επιστολή του στο Πατριαρχείο Κωνσταντινουπόλεως με ημερομηνία 25-7-1898 αιτούνταν την έγκριση αυτής της προσπάθειας, ενώ σημείωνε ότι θα υιοθετούσε κάθε υπόδειξη που θα γινόταν στη συγκεκριμένη έκδοση. Η Ιερά Σύνοδος του Οικουμενικού Πατριαρχείου παρέπεμψε το έργο στην αρμόδια επιτροπή η οποία ανέφερε σε έκθεσή της με ημερομηνία 30-10-1898 την οποία υπέβαλλε στο Πατριαρχείο ότι η μετάφραση έγινε «μετά πλείστης όσης και επαινετής επιμελείας και προσοχής». Όμως, τόνιζε ότι χρειάζονταν να εγκριθεί όπως η κανονική τάξη επέβαλε και από την Ιερά Σύνοδο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος. Η επιτροπή επιθυμούσε να φύγουν από τη μετάφραση οι σημειώσεις εντός παρενθέσεως και να τεθούν στο τέλος του βιβλίου ή στο κάτω μέρος κάθε σελίδας, και να μην υπάρχει ο πρόλογος και η εισαγωγή. Ως προς τις προσευχές υπήρχε διαφωνία μεταξύ των μελών. Ο πρόεδρος μαζί με τον μέγα αρχιδιάκονο ζητούσε οι προσευχές να μην υπάρχουν μέσα στο βιβλίο αλλά να εκδοθούν σε ειδικό τεύχος. Η Ιερά Σύνοδος του Πατριαρχείου Κωνσταντινουπόλεως έστειλε επιστολή στο Σύλλογο «Ανάπλασις», με αντίγραφο της εκθέσεως της Πατριαρχικής Κεντρικής Εκκλησιαστικής Επιτροπής συνοδευόμενη από σημείωμα με διάφορες παρατηρήσεις που αφορούσαν στη διόρθωση ορισμένων χωρίων, υπενθυμίζοντας την υποχρέωσή τους να στείλουν το έργο ξανά στο Πατριαρχείο για να ελέγξει εάν ακολούθησαν τις οδηγίες του. Οι υπεύθυνοι αφού προέβησαν στις απαραίτητες αλλαγές το έστειλαν στο Πατριαρχείο για να λάβουν την τελική έγκριση, η οποία δόθηκε με έκδοση σχετικής εγκυκλίου. Συνιστούσε μάλιστα την απόκτηση της εν λόγω εκδόσεως για την πνευματική ωφέλεια των Ορθοδόξων Χριστιανών που θα προέκυπτε από την μελέτη του έργου «και των εν αυτώ ορθών ερμηνειών και προσευχών», στις περιοχές που ήταν κάτω από την επίβλεψη του Οικουμενικού Θρόνου. Το Ευαγγέλιον, ως έκδοση του Συλλόγου «Ανάπλασις», κυκλοφορούσε με ερμηνευτική παράφραση (όχι μετάφραση) από το 1900. Από γλωσσικής απόψεως η συγκεκριμένη ερμηνευτική παράφραση έγινε στην απλή καθαρεύουσα (14).

Εκείνη την περίοδο μητροπολίτης Αθηνών και προκαθήμενος της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος ήταν ο Προκόπιος Β’ Οικονομίδης τον οποίο εξέλεξε στις 11-10-1896 η Ιερά Σύνοδος της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος μετά από συντονισμένες ενέργειες των ανακτόρων. Ο νέος μητροπολίτης των Αθηνών ήταν καθηγητής της Θεολογικής Σχολής του Πανεπιστημίου Αθηνών και των θρησκευτικών στους νεαρούς πρίγκιπες και στον διάδοχο του θρόνου Κωνσταντίνο. Η χειροτονία του στον τρίτο βαθμό της ιερωσύνης έγινε στις 17-10-1896. Υπήρξε φανατικός φιλοβασιλικός και υποστηρικτής της βασιλικής οικογένειας, ενώ παρέμεινε σε ολόκληρη την διάρκεια της θητείας του προσκολλημένος σε αυτήν σε τέτοιο βαθμό που το πλήρωσε με τον θρόνο του (15). Η εκλογή που έγινε με τις καθιερωμένες ωμές επεμβάσεις του κράτους στα εσωτερικά του εκκλησιαστικού οργανισμού, στον απόηχο της προσπάθειας της τσαρικής Ρωσίας να ιδρύσει με τη Συνθήκη του Αγίου Στεφάνου την Μεγάλη Βουλγαρία και έχοντας ως αποτέλεσμα να εκτοξευθεί ο αντισλαβισμός και να τονωθεί έντονα το εθνικό φρόνημα των Ελλήνων που υποπτεύονταν ότι πίσω από κάθε ενέργεια βρισκόταν η Ρωσία. Όταν οι Βούλγαροι το έτος 1885 προσάρτησαν την Ανατολική Ρωμυλία εκδιώκοντας τους Έλληνες, η κατάσταση ήταν έκρυθμη στο εσωτερικό της χώρας. Ο θάνατος του μητροπολίτη Αθηνών Γερμανού Καλλιγά (18-1-1896) άφησε κενό τον μητροπολιτικό θρόνο της πρωτεύουσας, αφού η κυβέρνηση του Θεόδωρου Δηλιγιάννη δεν επεδείκνυε καμία βιασύνη για την αντικατάστασή του. Η σύνθεση της Ιεράς Συνόδου εκείνης της περιόδου δεν βοηθούσε στην ανάδειξη του εκλεκτού του κράτους «δι’ απ’ ευθείας» προαγωγής. Όταν τον Οκτώβριο του 1896 οι συνθήκες για την πολιτεία υπήρξαν ευνοϊκές, εκλέγεται ο αρχιμανδρίτης Προκόπιος Οικονομίδης. Ο νέος προκαθήμενος προσπάθησε να ενισχύσει τη μόρφωση των υποψηφίων ιερέων με τη λειτουργία της Γερμάνειας Σχολής, ενώ έδειξε ιδιαίτερο ενδιαφέρον για κατήχηση του λαού. Ο Α. Πανώτης σημειώνει: «Επίσης, θέλησε να υπερκεράσει τη δράση των Ευαγγελικών του Καλαποθάκη στη διάδοση του Ευαγγελίου μεταξύ του λαού και για τον λόγο αυτόν τάχθηκε υπέρ της μεταφράσεως της Καινής Διαθήκης σε γλώσσα κατανοητή από τα λαϊκά στρώματα. Τον απασχολούσε ως ιεράρχη και καθηγητή η ανάπτυξη του αγιογραφικού κηρύγματος και της κατηχήσεως σε νεότερες γενεές, οι οποίες επηρεάζονταν από καινοφανείς θεωρίες, όπως εκείνες του δαρβινισμού και του ιστορικού υλισμού» (16).

Το Πατριαρχείο Κωνσταντινουπόλεως τα έτη 1898-1899 αποφάσισε τη σύσταση επιτροπής που θα αναλάμβανε την έκδοση του πρωτότυπου κειμένου της Καινής Διαθήκης και θα περιελάμβανε την «κατά το ενόν αποκατάστασιν του αρχετύπου κειμένου της εκκλησιαστικής παραδόσεως και μάλιστα της Εκκλησίας Κωνσταντινουπόλεως». Η τριμελής επιτροπή απαρτιζόταν από το μητροπολίτη Σταυρουπόλεως Απόστολο, τον μητροπολίτη Σάρδεων Μιχαήλ και το καθηγητή της Θεολογικής Σχολής Χάλκης, Βασίλειο Αντωνιάδη, ο οποίος το 1904 εξέδωσε κριτικά την Καινή Διαθήκη μετά από έρευνα που διεξήγαγε σε περισσότερους από 125 κώδικες και είναι η μόνη κριτική έκδοση του κειμένου της Ορθόδοξης Ανατολικής Εκκλησίας. Το συγκεκριμένο κείμενο δεν είναι προσκολλημένο σε κανέναν κώδικα, ενώ χρησιμοποιήθηκαν τα εκλογάδια των Ευαγγελισταρίων και Πραξαποστόλων που χρησιμοποιούσαν καθημερινά στις Ορθόδοξες εκκλησίες. Η κριτική έκδοση του Αντωνιάδη έγινε με πολλές δυσκολίες, αφού δεν είχε σύγχρονα τυπογραφεία, όπως αυτά της γηραιάς ηπείρου για να τυπωθεί το έργο του. Στο κείμενο αυτό δεν υπάρχει κριτικό υπόμνημα αλλά ο ίδιος κατάφερε να τυπωθεί κάθε λέξη ή φράση που δεν υπήρχαν σε όλους του κώδικες με διαφορετικά στοιχεία. Η Ιερά Σύνοδος του Οικουμενικού Πατριαρχείου επέβαλε στον καθηγητή Αντωνιάδη τη διατήρηση του νόθου χωρίου Ιω. 5,7 που εισήγαγε στο ευαγγέλιο ο ρωμαιοκαθολικός καρδινάλιος Ximenes de Cisneros το οποίο δεν υπήρχε σε κανένα, χειρόγραφο, ενώ θεωρείται το καθαρότερο κείμενο και το πληρέστερο προς το αρχικό (17).

Η έναρξη της δημοσίευσης στην εφημερίδα Ακρόπολη του μεταγλωττισμένου στη δημοτική γλώσσα κατά Ματθαίον Ευαγγελίου από τον έμπορο Αλέξανδρο Πάλλη, κάτοικο του Λίβερπουλ, που μαζί με τον Ψυχάρη και τον Πάλλη υπήρξε στην εποχή του ο μαχητικός λόγιος- υπέρμαχος του δημοτικισμού, κατέληξε στα αιματηρά γεγονότα τα οποία έμειναν γνωστά στην ιστορία ως «Ευαγγελικά» ή «Ευαγγελιακά», εκείνη δε την περίοδο αναφέρονται και ως «Νοεμβριανά». Η εφημερίδα έγραφε ότι επιτελούσε ένα τεράστιο αναμορφωτικό έργο, αφού η ίδια διέδιδε μέσω των στηλών της το κήρυγμα του Χριστού «το οποίον μέχρι την σήμερον ήτο με πολλαπλάς σφραγισμένον σφραγίδας. Από της σήμερον δικαίως ως δυνάμεθα να επιφωνήσωμεν: Ούτω λαμψάτω το φως!». Ο Αλέξανδρος Πάλλης θέλησε να προσφέρει το ιερό κείμενο σε απλή γλώσσα κατανοητή από το ευρύ κοινό. Στο τέλος του 1900 εκδόθηκαν με φροντίδα της βασίλισσας Όλγας 1.000 αντίτυπα των τεσσάρων Ευαγγελίων μεταγλωττισμένα σε γλώσσα που μπορούσε να γίνει αντιληπτή. Η έκδοση ήταν σε δίστηλη μορφή και περιελάμβανε το πρωτότυπο ιερό κείμενο και δίπλα την απόδοσή του στη νεοελληνική την οποία είχε αναλάβει η γραμματέας της βασίλισσας Όλγας Ιουλία Σωμάκη (μετέπειτα σύζυγος Νικ. Καρόλου). Η Δέσποινα Μιχάλαγα γράφει: «Η έκδοση αν και δήλωνε ότι είχε συνταχθεί στην καθαρώς λαϊκή γλώσσα -την οποία μάλιστα υποστήριζε ότι δεν υπηρετούσε η ανάλογη της “Αναπλάσεως” δεν εκπλήρωνε τελικά τον στόχο της, ως “τείνουσα προς τον δημώδη λόγο, μετριωτέρα μορφή της καθαρευούσης”» (18).

Η μετάφραση των τεσσάρων Ευαγγελίων έγινε με τη βοήθεια του καθηγητή της Θεολογίας Φίλιππου Παπαδόπουλου. Το αποτέλεσμα αυτής της προσπάθειας απέστειλε η βασίλισσα Όλγα στον μητροπολίτη Αθηνών ο οποίος δέχθηκε τη δημοσίευσή της. Η βασίλισσα Όλγα στράφηκε και προς το αρμόδιο υπουργείο επί των εκκλησιαστικών και της δημοσίας εκπαιδεύσεως για να λάβει τη σχετική άδεια διανομής του βιβλίου εντός των σχολείων της ελληνικής επικράτειας. Όμως, ο αρμόδιος υπουργός Αντώνιος Μομφεράτος αντιλαμβανόμενος τη θύελλα που θα ξεσπούσε από μια τέτοια εξέλιξη, υπέδειξε τη λήψη της εγκρίσεως από την Ιερά Σύνοδο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος. Τον Δεκέμβριο του 1898 με επιστολή της η βασίλισσα προς την Ιερά Σύνοδο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος ζητούσε την άδεια της για την κυκλοφορία της μεταφράσεως. Τον Μάρτιο του 1899 η Ιερά Σύνοδος απέρριψε τη μετάφραση ως «γενομένην εν γλώσση δημώδει και τετριμμένη». Η βασίλισσα Όλγα, λίγους μήνες αργότερα, απαίτησε από τον προκαθήμενο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος να γίνει σύσκεψη παρουσία της των συνοδικών αρχιερέων, χωρίς να προκύψει κανένα θετικό αποτέλεσμα. Η στάση του μητροπολίτη Αθηνών δεν την ικανοποίησε και κατέφυγε στο Οικουμενικό Πατριαρχείο Κωνσταντινουπόλεως το οποίο αρνήθηκε να εμπλακεί. Ο Α. Πανώτης γράφει: «Ας σημειωθεί ότι η γλώσσα των Ευαγγελίων εθεωρείτο πάντοτε σύμβολο της διαχρονικής ενότητος τους ελληνισμού. […] Γι’ αυτό και η μετάφραση του Ευαγγελίου εξελίχθηκε σε διαμάχη ιδεών για την ανατροπή του τότε σκοταδισμού» (19).

Ο δημοσιογράφος Βλάσης Γαβριηλίδης διευθυντής της εφημερίδας Ακρόπολις, υποστηρικτής της δημοτικής γλώσσας, δημοσίευσε στο έντυπό του στις 9-9-1901 ως συνέχεια του έργου της βασίλισσας Όλγας μια νέα μετάφραση του κατά Ματθαίου Ευαγγελίου που έγινε από τον Αλέξανδρο Πάλλη. Η κίνηση αυτή ξεσήκωσε θύελλα αντιδράσεων για το λεξιλόγιο που χρησιμοποίησε ο μεταφραστής. Στις 3 Νοεμβρίου οι δημοσιεύσεις στα έντυπα έχουν ανάψει τα αίματα. Ο μητροπολίτης Προκόπιος Β’ αντιλαμβανόμενος το χάος που θα επακολουθούσε εκδίδει απόφαση της Ιεράς Συνόδου για να ηρεμήσει κυρίως τον φοιτητόκοσμο.

«Αριθμ. Πρωτ. 317-697

Περί αποδοκιμασίας και κατακρίσεως πάσης μεταφράσεως του Ιερού Ευαγγελίου εις απλουστέραν Ελληνική γλώσσαν.

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΙΟΝ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΑΔΟΣ Η ΙΕΡΑ ΣΥΝΟΔΟΣ ΤΗΣ ΕΚΚΛΗΣΙΑΣ ΤΗΣ ΕΛΛΑΔΟΣ

Προς τους ανά το κράτος Σεβ. Ιεράρχας και την Επισκοπικήν Επιτροπήν Μεσσηνίας

Από της θεοπνεύστου συγγραφής του Ιερού Ευαγγελίου και μέχρι μεσούντος του 17ου αιώνος ουδείς πότε διενοήθη ή εξήνεγκε γνώμην περί μεταφράσεως αυτού εις γλωσσικόν ιδίωμα απλούστερον και ευληπτότερον της γλώσσης, εις ην, θεία προνοία, υπό μεν των Ευαγγελιστών εγράφη, υπό δεν τον Αποστόλων και των διαδόχων αυτών εκηρύχθη, και ήτις εχρησίμευε θαυμασίως εις τε την παγκόσμιον διάδοσιν της αγίας και θεοτεύκτου ημών θρησκείας και εις την κρατεράν και πάντοτε νικηφόρον αυτής άμυναν κατά πολλών και πολυειδών διωγμών και επιβουλών.

Κατά Μάιον του 1629 μ.Χ. εξηνέχθη πρώτην φοράν γνώμη περί μεταφράσεως της Κ. Διαθήκης εις την τότε δημοτικήν Ελληνικήν γλώσσαν, και αύτη ουχί παρ’ Έλληνος ή Ορθοδόξου Χριστιανού, αλλά παρ’ Ολλανδού καλβινιστού ιερέως, ταύτη δ’ επηκολούθησαν έκτοτε όμοιαι, ευάριθμοι, αλλά πάντοτε ατέλεστοι και θνησιγενείς απόπειραι. Η Ελληνική Ορθόδοξος του Χριστού Εκκλησία, μόνη κεκτημένη εν τη εαυτής γλώσση το επίσημον της Κ. Διαθήκης κείμενον, αυτό το πρωτότυπον και αρχέτυπον, έσχε πάντοτε πλήρη συναίσθησιν του τιμαλφούς τούτου πνευματικού προνομίου και δεν επέτρεψε την εις αυτό υποκατάστασιν οιασδήποτε μεταφράσεως. Βάσιν και θεμέλιον ασάλευτον έχουσα την ανέκαθεν παραδοθείσαν αυτή πολύτιμον ιεράν κληρονομίαν υπό των Αποστόλων, των Οικουμενικών Συνόδων, των Αγίων Πατέρων και των εν γένει Εκκλησιαστικών παραδόσεων, των αρραγώς τεθεμελιωμένων επί τα πάτρια θέσμια, τα θαυμασίως υπό της Ιστορίας κυρωθέντα, απεκήρυξε και απέκρουσεν ως έργον οθνείον και άθεσμον πάσαν καινοσπούδου εφέσεως επιχείρησιν προς εκτροπήν από της ούτε κεχαραγμένης βασιλικής οδού, ην εν τη μακραίωνι αυτής πορεία νικηφόρως πάντοτε εβάδισε. Τοιούτων εφέσεων τοιαύται επιχειρήσεις εισί και αι μέχρι του νυν απόπειραι μεταφράσεως του ιερού Ευαγγελίου εις απλουστέραν Ελληνικήν γλώσσαν, εσχάτως δε και εις οικτρώς κακόζηλον και χυδαϊκήν, αηδώς και σκανδαλωδώς παραμορφούσαν το σεμνόν κάλλος του θεοπνεύστου αρχετύπου κειμένου.

Η Ελληνική Ορθόδοξος Εκκλησία παγίως απεφήνατο, ότι τας υψηλάς και σωτηρίους του Ευαγγελίου εννοίας αδύνατον είναι να αποδώση οιαδήποτε μετάφρασις, απλώς τας λέξεις αντικαθιστώσα δι’ άλλων ευληπτοτέρων, διότι ούτως απειλείται διαστροφή των εννοιών, αίτινες ανεπτύχθησαν και διετυπώθησαν εις δόγματα παρά Οικουμενικών Συνόδων. Την επιζήτησιν πληρεστέρας και σαφεστέρας του ιερού Ευαγγελίου κατανοήσεως η Ορθόδοξος Εκκλησία, ου μόνον ουδέποτε απηγόρευσεν, αλλά και πάντοτε μεν συνέστησεν, ενίοτε δε και επέβαλεν, ουχί όμως διά μεταφράσεων, αλλά διά των κανονικών ανεγνωρισμένων και καθηγιασμένων ερμηνειών των Αγίων Πατέρων και των μεγάλων αυτής διδασκάλων ως και πάσης άλλης από των διαυγών αυτών πηγών ηντλημένης, και υπ’ αυτής της Εκκλησίας μετά έλεγχον εγκεκριμένης.

Συνωδά τούτοις η Ορθόδοξος Εκκλησία απεδοκίμασε και ανεθεμάτισεν ουχί άπαξ πάσαν οιανδήποτε μετάφρασιν του Ιερού Ευαγγελίου εις απλουστέραν γλώσσαν διά τε Συνοδικών όρων και διά Πατριαρχικών και Συνοδικών αποφάσεων και εγκυκλίων. Παρά ταύτα όμως πάντα, τολμώνται και μέχρι των ημερών ημών μεταφράσεις του ιερού Ευαγγελίου, υπαγορευόμεναι εκ σφαλεράς ίσως προαιρέσεως του καταστήσαι αυτό προσιτώτερον και ευνοητότερον τω λαώ. Οι τοιαύτα επιχειρούντες αντιστρατεύονται τοις θεσμίοις και ταις διαταγαίς της Ορθοδόξου Εκκλησίας, ήτις, επί πάσι τοις ήδη λεχθείσιν, ουδέποτε εν τη σχεδόν δισχιλιετεί αυτής πείρα σύνοιδεν ως αναγκαίον επικουρικόν μέσον προς πληρεστέραν του ιερού Ευαγγελίου κατανόησιν την εις απλουστέραν γλώσσαν μετάφρασιν αυτού αλλ’ απεδοκίμασε και ανεθεμάτισεν αυτήν.

Η Ελληνική Ορθόδοξος του Χριστού Εκκλησία, η ουδέποτε ευτυχώς σφαλείσα των ορθών βουλευμάτων εν τω υπέρ της αγνότητος και κραταιώσεως αυτής αγώνι, ως έχουσα άνωθεν ορθήν συνείδησιν και αντίληψιν των υψίστων του πληρώματος αυτής συμφερόντων, ουδέ εν αυτοίς έτι τοις ζοφερωτάτοις χρόνοις του σκότους των διωγμών και της δουλείας ησθάνθη ανάγκην, ίνα το πιστόν αυτής πλήρωμα ποτισθή τα σωτήρια νάματα του Ευαγγελίου υπό τύπον και μορφήν άλλην παρά την παραδοθείσαν αυτή από των Αποστολικών χρόνων.

Αι από χιλιετηρίδος και πλέον υφιστάμεναι διαφοραί της γλώσσης του Ευαγγελίου από της λαλουμένης, αίτινες εν των παρελθόντι ήσαν ομολογουμένως πολύ βαθύτεραι και σπουδαιότεραι των εν τω παρόντι, ουδέποτε επεσκότισαν το παράπαν τας ψυχάς των ακροατών ή αναγνωστών αυτού, ουδ’ εμείωσαν τον προς αυτό σεβασμόν και την υπακοήν εις τα θεόπνευστα αυτού ρήματα, προσιτά και καρποφόρα αείποτε υπάρξαντα εις πάσαν χριστιανική διάνοιαν και καρδίαν. Της εθνικής δ’ ημών γλώσσης οσημέραι προαγομένης, και βραδέως μεν ίσως, αλλ’ ασφαλώς και αισίως χωρούσης προς την πάλαι αυτής ακμήν και το μεγαλείον, ουδεμία κατά μείζονα λόγον υφίσταται τα νύν ανάγκη, ένεκα ελαχίστων και σχεδόν ήδη ανεπαισθήτων διαφορών, να αλλοιωθή ο απ’ αιώνων παραδεδόμενος ημίν τύπος των υψηλών και θεοπνεύστων επών του Ευαγγελίου, ο από δισχιλίων ετών βαθύτατα εκκολαφθείς εις τε τον νουν και τας καρδίας ημών και εις πάσας τας εκδηλώσεις του θρησκευτικού ημών βίου. Συμφώνως προς ταύτα, η Ιερά Σύνοδος της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος, στερρώς προσκειμένη τοις πατροπαραδότοις θεσμίοις και τη αρχήθεν ομοφώνω και διά των αιώνων απαρασαλεύτω μέχρι νυν γνώμη της Ορθοδόξου Εκκλησίας, φύλαξ δε άγρυπνος των ιερών εκκλησιαστικών παραδόσεων, της ετέρας ταύτης διαυγούς και ζωηφόρου πηγής της χριστιανικής θρησκείας ων την τήρησιν ενεπιστεύθησαν αυτή οι τε εκκλησιαστικοί θεσμοί και οι πολιτικοί νόμοι, αποκρούει και αποδοκιμάζει και κατακρίνει ως βέβηλον πάσαν διά μεταφράσεως εις απλουστέραν ελληνικήν γλώσσαν αλλοίωσιν ή μεταβολήν του πρωτοτύπου κειμένου του Ιερού Ευαγγελίου, ου μόνον ως περιττήν, αλλά και ως έκθεσμον και συντελούσαν εις σκανδαλισμόν μεν των συνειδήσεων, στρέβλωσιν δε των θείων αυτού εννοιών και διδαγμάτων.

Εντέλλεται δ’ Υμίν και δι’ Υμών παντί τω κλήρω, ίνα, εξ ονόματος αυτής, συνιστάτε πάντοτε τω καθ’ υμάς ποιμνίω διά πατρικών νουθεσιών και προτροπών, όπως μηδείς μηδέποτε αναγινώσκη μετάφρασιν οιανδήποτε του Ιερού Ευαγγελίου, ως απηγορευμένην και καταδεδικασμένην υπό της Εκκλησίας.

Της παρούσης αποστέλλονται Υμίν ικανά αντίτυπα, ίνα διανεμηθώσι τοις υφ’ Υμάς κληρικοίς, αναγνωσθώσι δ’ ευκρινώς και επ’ Εκκλησίας.

Απεφασίσθη μεν τη εβδόμη και δεκάτη μηνός Οκτωβρίου, εξεδόθη δε την εβδόμη μηνός Νοεμβρίου σωτηρίου έτους 1901 εν Αθήναις.

†ο Αθηνών Προκόπιος, Πρόεδρος

† Ο Σύρου, Τήνου και Άνδρου Μεθόδιος

† Ο Ύδρας και Σπετσών Αρσένιο

† Ο Τριφυλίας και Ολυμπίας Νεόφυτος

† Ο Παροναξίας Γρηγόριος

Ο Γραμματεύς Αρχιμ. Μελέτιος Σακελλαρόπουλος (20).

Η μετάφραση του Αλέξανδρου Πάλλη σταμάτησε να δημοσιεύεται στην εφημερίδα «ΑΚΡΟΠΟΛΙΣ» στις 20-10-1901 μετά την ολοκλήρωση του κατά Ματθαίον Ευαγγελίου, εξαιτίας της αναστάτωσης που είχε προηγηθεί. Η εφημερίδα σημείωνε ότι συνέχιζε το έργο της βασίλισσας Όλγας. Ο Αλέξανδρος Πάλλης γεννήθηκε το έτος 1851 στον Πειραιά, ενώ το 1869 έφυγε για το Manchester όπου ασχολήθηκε με το εμπόριο και έζησε στο εξωτερικό για 66 χρόνια. Εμφανίσθηκε στα γράμματα το 1879, γράφοντας στην καθαρεύουσα μέχρι το έτος 1888 και γίνεται από τους πρώτους οπαδούς του Ψυχάρη μαζί με τον Α. Εφταλιώτη που κατοικούσε στο Manchester. Ο Ε. Κωνσταντινίδης γράφει: «Εις την εν τη “Ακροπόλει” δημοσιευομένην μετάφρασίν του ο Πάλλης εφαρμόζει το γλωσσικόν του “πιστεύω” και το γραμματικόν του σύστημα, αδιαφορών διά τας αντιδράσεις των “αρχαϊστών”. Χρησιμοποιεί τοιουτοτρόπως: συστηματικούς νεολογισμούς, περιττούς ιδιωματισμούς και αστόχους φωνητικάς εξομαλύνσεις» (21).

Η ρωσική διπλωματία, ενημερωμένη για τις αντιδράσεις των Ορθόδοξων Ελλήνων για την μετάφραση του ιερού κειμένου σε απλή γλώσσα, εκφράζει με σαφή τρόπο τη δυσφορία του ρωσικού λαού και τη στάση του εγχώριου τύπου. Η τοποθέτησή τους φανερώνει ότι αντιλαμβάνονταν τις κινήσεις αυτές ως μια οργανωμένη αντιρωσική και αντισλαβική τακτική που είχαν υιοθετήσει οι Έλληνες στηριζόμενοι σε δύο γεγονότα που ερμηνεύονταν μέσα από συγκεκριμένη οπτική. Το πρώτο είναι συμβολικού χαρακτήρα και αφορά στην απόφαση των Ελλήνων να τελέσουν επιμνημόσυνη δέηση υπέρ αναπαύσεως των ψυχών των Άγγλων πεσόντων στον πόλεμο κατά των Μπόερς. Η Ιερά Σύνοδος δεν είχε δώσει την απαιτούμενη άδεια να τελεσθούν τα ιερά μνημόσυνα για όσους ανήκαν σε άλλα δόγματα. Η τσαρική Ρωσία αντιλαμβανόταν αυτή τη συγκεκριμένη εξέλιξη ως κίνηση που αποδείκνυε ότι οι νεοέλληνες στρέφονταν προς τον βρετανικό παράγοντα για να αντλούν βοήθεια. Η προσέγγιση μεταξύ Ελλάδας και Ρουμανίας δεν άφηνε πολλά περιθώρια ερμηνείας, αφού η ύπαρξη ενός αντιρωσικού μετώπου ήταν υπαρκτή για εκείνους. Μέσα σε αυτό το πλαίσιο τα δημοσιεύματα στον Τύπο και η στάση κάποιων πολιτικών ταγών βοηθούν στην αποστασιοποίηση του απλού λαού από το ρωσικό παράγοντα ο οποίος χρησιμοποιεί τον όρο «πανσλαβισμός» για να περιγράψει τη στάση της τσαρικής Ρωσίας στο διεθνές σκηνικό. Οι Έλληνες υποψιάζονταν, όπως φαίνεται από τις στήλες των εντύπων, την τσαρική Ρωσία από το έτος 1852 ότι προσπαθούσε «να καταβροχθίσει εις πρώτην ευκαιρίαν την Βυζαντινήν αυτοκρατορίαν». Ένα άλλο μείζονος σημασίας γεγονός ήταν αργότερα τα αιματηρά γεγονότα των Ευαγγελικών, η εκλογή στον πατριαρχικό θρόνο της Αντιόχειας του Άραβα πατριάρχη Μελετίου και η έντονη σύγκρουση του ελληνικού και ρωσικού παράγοντα για το ζήτημα της απογείωσης του σλαβικού εθνικισμού όπως έγινε στην περίπτωση των Βουλγάρων. Η Άντα Διάλλα σημειώνει: «Τα Ευαγγελικά ήταν μια οξεία εκφορά της συζήτησης για το εθνικό ζήτημα, την εθνική ταυτότητα και το αιτούμενο του προσδιορισμού ή του αναπροσδιορισμού της μετά την τραυματική ήττα του 1897. Γλώσσα και θρησκεία/ορθοδοξία θεωρούνταν θεμελιώδη συστατικά της Ελληνικότητας» (22).

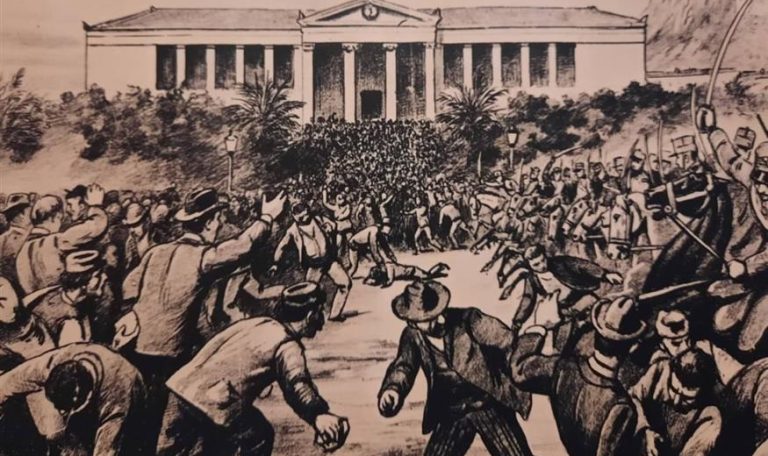

Οι φοιτητές του πανεπιστημίου που αντέδρασαν πρώτοι ήταν αυτοί της ιατρικής σχολής. Στις 5 Νοεμβρίου 1901 ανέλαβαν δράση για να αποτρέψουν «την περαιτέρω διακωμώδησιν του Ιερού μας Ευαγγελίου και της υψηλής ημών γλώσσης». Στη συνέχεια, και οι φοιτητές των υπολοίπων σχολών ξεσηκώθηκαν, κατευθύνθηκαν στα Προπύλαια του πανεπιστημίου για να συνεχίσουν την πορεία τους στα γραφεία της εφημερίδας «Ακρόπολις» φωνάζοντας και καίγοντας τα φύλλα. Στη συνομιλία τους με τον αρχισυντάκτη της εφημερίδας Γ. Πωπ απαίτησαν το έντυπο να αναιρέσει όσα είχε γράψει για τη Θεολογική Σχολή Αθηνών. Η πορεία συνεχίστηκε στα γραφεία της εφημερίδας «Άστυ» η οποία δημοσίευσε την απάντηση του Αλέξανδρου Πάλλη προς την εγκύκλιο του Πατριαρχείου Κωνσταντινουπόλεως. Τέλος, οι φοιτητές επισκέφθηκαν τον μητροπολίτη Αθηνών Προκόπιο Β’, ο οποίος δήλωσε ότι δεν θα επιτρεπόταν η αλλοίωση του κειμένου της Βίβλου. Την επομένη ημέρα οι φοιτητές επισκέφθηκαν ξανά τις ίδιες εφημερίδες διότι δεν είχαν αναιρέσει όσα είχαν γράψει τις προηγούμενες ημέρες. Ο πρύτανης Σ. Σακελλαρόπουλος ζητούσε από τους φοιτητές του Πανεπιστημίου να περιφρουρήσουν την τιμή του ιδρύματος. Η εφημερίδα «Ακρόπολις» δέχθηκε μόνο την αναίρεση των σχολίων της για τη Θεολογική Σχολή Αθηνών. Εκείνη την ημέρα οι χωροφύλακες έκαναν την εμφάνισή τους συνοδευόμενοι από διάφορες φήμες για την κατάληψη του ιδρύματος από αυτούς. Στις 7 Νοεμβρίου 1901 συγκεντρώθηκαν ξανά οι φοιτητές στο Προπύλαια και αρνήθηκαν να ακολουθήσουν τις υποδείξεις της συγκλήτου του ιδρύματος για να διαλυθούν. Την ίδια ημέρα η Ιερά Σύνοδος με έγγραφό της αποδοκίμαζε κάθε μεταφραστική προσπάθεια. Όμως, οι φοιτητές ήθελαν να μεταβούν στο κτήριο της Ιεράς Συνόδου, ζητώντας τον αφορισμό των μεταφραστών, χωρίς να καταφέρουν να φθάσουν αφού οι χωροφύλακες δεν τους το επέτρεψαν. Στις 8 Νοεμβρίου 1901 οι φοιτητές είχαν αρχίσει να συγκεντρώνονται στον ίδιο χώρο από το πρωί, διαβάζοντας στην τοιχοκολλημένη διαταγή της χωροφυλακής την απαγόρευση των διαδηλώσεων. Οι διαδηλωτές δεν υπάκουσαν και με ψήφισμά τους ήθελαν τον αφορισμό των μεταφραστών. Λίγο πριν διαλυθεί η συγκέντρωση η πρόταση κάποιων να κατευθυνθούν «Εις του Μητροπολίτη» έφερε το χάος.

Οι διαδηλωτές αποκρούστηκαν από τη χωροφυλακή και έγιναν συμπλοκές με αποτέλεσμα να υπάρξουν νεκροί και τραυματίες. Πολλοί από τους διαδηλωτές γύρισαν πίσω στα Προπύλαια ζητώντας να τους δώσουν οι φοιτητές τα όπλα της φοιτητικής φάλαγγας. Στα επεισόδια ακούσθηκαν πάλι πυροβολισμοί και συμπλοκές ιππικού και φοιτητών, ενώ κάποιοι φώναξαν υπέρ του διαδόχου Κωνσταντίνου και της συζύγου του Σοφίας, δείχνοντας την αποστροφή τους προς το πρόσωπο της ρωσικής καταγωγής βασίλισσας Όλγας. Τα τραγικά γεγονότα που σημειώθηκαν άφησαν οκτώ νεκρούς και από εβδομήντα ως ογδόντα τραυματίες. Η ελληνική κυβέρνηση υπό το βάρος των γεγονότων δεν μπορούσε να συνεχίσει. Στις 10 Νοεμβρίου η κυβέρνηση Γ. Θεοτόκη παραιτήθηκε όπως και ο μητροπολίτης Αθηνών Προκόπιος Β’ και ο διευθυντής της αστυνομίας (23).

Ο δημοτικισμός μπορεί στην αυγή του 20ού αι. να ηττήθηκε από την καθαρεύουσα αλλά μια δεκαετία αργότερα ήταν κάτι περισσότερο από μια γλωσσική μεταρρύθμιση για τα ελληνικά πράγματα. Σχετιζόταν με ευρύτερες και ποικίλες ζυμώσεις, σε μια εποχή που η έκτασή του ελληνικού κράτους όπως και ο πληθυσμός του σχεδόν θα διπλασιάζονταν. Η διασφάλιση της καθαρεύουσας επομένως ήταν σε πρώτη προτεραιότητα. Μετά το κίνημα στο Γουδί το πολιτικό σκηνικό στην Ελλάδα θα αλλάξει. Η είσοδος του Ελ. Βενιζέλου στην πολιτική ζωή έφερε σύντομα την πλειονότητα των οπαδών της δημοτικής γλώσσας στο πλευρό του με στόχο την επικράτησή της στον χώρο της πρωτοβάθμιας και της δευτεροβάθμιας εκπαίδευσης. Το κίνημα των δημοτικιστών οδήγησε σε ιδεολογική πόλωση και δεν θα αργήσει να ταυτιστεί με τον αριστερό χώρο, και απέρριπτε το τρίπτυχο πατρίς, θρησκεία, οικογένεια. Ο Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος δεν ικανοποίησε αρχικά τους οπαδούς του, γνωστούς υποστηρικτές της δημοτικής γλώσσας, αφού με το σύνταγμα του 1911 επιλέγει την απλή καθαρεύουσα. Μετά τον διαμελισμό του ελληνικού κράτους και την ύπαρξη δύο κυβερνήσεων με έδρα της βασιλικής κυβερνήσεως την Αθήνα και της Προσωρινής Κυβέρνησης στη Θεσσαλονίκη, οι δημοτικιστές ανέλαβαν δράση. Ο Δημήτρης Γληνός, ιθύνων νους της εκπαιδευτικής μεταρρύθμισης, καταφέρνει την εισαγωγή της δημοτικής γλώσσας στην εκπαίδευση. Με την επανένωση του ελληνικού βασιλείου και την επικράτηση του κόμματος των Φιλελευθέρων στα πολιτικά πράγματα της χώρας, η νέα κυβέρνηση εκμεταλλεύθηκε κάποιες καταστάσεις που της επέτρεψαν να προχωρήσει σε κάποιες αλλαγές, ανέφικτες σε άλλες περιστάσεις, όπως την παράκαμψη του Εκπαιδευτικού Συμβουλίου της Φιλοσοφικής σχολής και την παραχώρηση της εκπαιδευτικής πολιτικής του νεοελληνικού κράτους σε ένα απλό σωματείο, τον Εκπαιδευτικό Όμιλο, γνωστό για τις επιλογές των μελών του. Τον Σεπτέμβριο του 1917 θα προσληφθούν ως Ανώτεροι Επόπτες Δημοτικής Εκπαίδευσης ο Αλέξανδρος Δελμούζος και ο Μανώλης Τριανταφυλλίδης υποστηρικτές της δημοτικής γλώσσας. Αυτοί ασχολήθηκαν με την έκδοση νέων βιβλίων για την πρωτοβάθμια εκπαίδευση προσαρμοσμένα στους σκοπούς της γλωσσικής μεταρρύθμισης, προβαίνοντας παράλληλα και στις κατάλληλες υποδείξεις στους συγγραφείς (24).

Η εκπαιδευτική μεταρρύθμιση έλαβε χώρα με τους νόμους 826/2-91917 και 827/2-9-1917. Ο νέος υπουργός επί των εκκλησιαστικών και δημοσίας εκπαιδεύσεως έσπευσε να συμπληρώσει και να επικυρώσει ένα από τα διατάγματα της Προσωρινής Κυβέρνησης Θεσσαλονίκης το οποίο επεξέτεινε σε ολόκληρη την ελληνική επικράτεια και αφορούσε στα σχολικά εγχειρίδια τα οποία θα έπρεπε να είχαν εγκριθεί βασιζόμενα στους νέους νόμους, ενώ για τα σχολικά βιβλία του μαθήματος των θρησκευτικών οι εκδότες και οι συγγραφείς θα έπρεπε να είχαν και πάλι την έγκριση της Ιεράς Συνόδου της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος. Με τον νέο νόμο ο υπουργός Δημήτριος Δίγκας καθιέρωσε στην ιστορία της νεοελληνικής εκπαίδευσης τη δημοτική γλώσσα στις τέσσερις πρώτες τάξεις της πρωτοβάθμιας εκπαίδευσης. Στις πρώτες αυτές τάξεις του δημοτικού έπρεπε να χρησιμοποιείται μόνο το αναγνωστικό βιβλίο, χωρίς να υπάρχει ίχνος αρχαϊσμού. Μοναδική εξαίρεση αποτελούσαν η έκδοση της Καινής Διαθήκης του Οικουμενικού Πατριαρχείου Κωνσταντινουπόλεως και οι εκδόσεις Ελλήνων και Λατίνων συγγραφέων Teubner της Λειψίας (25).

Ο νόμος 827/1917 τροποποιήθηκε από το νόμο 1332/16-4-1918 ο οποίος καθιέρωσε τη διδασκαλία της δημοτικής γλώσσας σε ολόκληρο το εξατάξιο δημοτικό σχολείο με παράλληλη τη διδασκαλία στις δύο τελευταίες τάξεις της καθαρεύουσας. Τα δύο αναγνωστικά βιβλία του δημοτικού σχολείου «Τα ψηλά βουνά» και «Αλφαβητάρι με τον Ήλιο» διαπνέονταν από μια διαφορετική νοοτροπία και αντίληψη από αυτήν που υπήρχε στο εκπαιδευτικό σύστημα της χώρας πριν από τη μεταρρύθμιση. Σύμφωνα με την Άννα Φραγκουδάκη και τον Αλέξη Δημαρά αντανακλούσαν την ιδεολογία του αστικού ορθολογισμού (26). Ο Χάρης Αθανασιάδης σημειώνει: «Ωστόσο, η εισαγωγή «Των ψηλών βουνών» στα σχολεία λειτούργησε ως θρυαλλίδα για την εκδήλωση πολλαπλών και ισχυρών αντιδράσεων, παρότι το ενδιαφέρον του Τύπου ήταν πρωτίστως στραμμένο στο συνέδριο του Παρισιού. Ή ίσως ακριβώς για αυτό: […] η διαμάχη για το βιβλίο δεν ήταν τόσο άσχετη με το εθνικό ζήτημα, όσο από πρώτη άποψη μοιάζει» (27).

Οι εξελίξεις αυτές στο γλωσσικό ζήτημα που τόσο έντονα απασχολούσαν τους κύκλους των διανοουμένων από τις δύο τελευταίες δεκαετίες του 19ου αιώνα δεν άφησαν αδιάφορους τους οπαδούς της καθαρεύουσας ούτε τον εκκλησιαστικό οργανισμό. Οι αντιδράσεις υπήρξαν αναμενόμενες, παρόλο που η πολιτική κατάσταση δεν το επέτρεπε. Στις 29 Μαΐου 1917 αποβιβάζεται γαλλικός στρατός στην πρωτεύουσα και αναγκάζει τον βασιλιά Κωνσταντίνο Α’ να παραιτηθεί από τον θρόνο υπέρ του δευτερότοκου γιου του πρίγκιπα Αλεξάνδρου και αναχωρεί από την Ελλάδα για το εξωτερικό. Μετά την εκθρόνιση του Κωνσταντίνου Α’ και την κάθοδο στην πρωτεύουσα της Προσωρινής Κυβέρνησης της Θεσσαλονίκης, αναβίωσε η Βουλή του 1915, η λεγομένη «Βουλή των Λαζάρων» και το Ελληνικό κράτος επανενώθηκε. Στις 14-7-1917, ο Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος εγκαθιδρύει ενιαία κυβέρνηση και κηρύσσει τον πόλεμο εναντίον των εχθρών της Εγκάρδιας Συμμαχίας. Στη συνέχεια, εξορίζει πολιτικούς του αντιπάλους και στρατιωτικούς, νομοθετεί την λογοκρισία στον Τύπο, απολύει φιλοβασιλικούς καθηγητές του πανεπιστημίου, αίρει την μονιμότητα των δικαστών, συντρίβει στάσεις σε Λαμία και Θήβα, απολύει αξιωματικούς της χωροφυλακής και απλούς χωροφύλακες καθώς και δικαστικούς λειτουργούς και αναζητεί τρόπο να εξομαλυνθούν οι σχέσεις του με τον νεαρό Βασιλιά Αλέξανδρο Α’ και το επιτυγχάνει πολύ σύντομα (28).

Η κατάσταση που είχε οδηγηθεί η χώρα με τη συνδρομή των πολιτικών δυνάμεων του τόπου έφερε δυστυχώς τον εθνικό διχασμό σε μια πολύ δύσκολη περίοδο. Οι εκκλησιαστικοί άνδρες ακολούθησαν τον δρόμο που χάραξαν οι πολιτικοί ταγοί του έθνους και τον ολοκλήρωσαν με τον εκκλησιαστικό διχασμό, όπου με την τροπή την οποία είχαν λάβει τα πράγματα ήταν αδύνατον να αποφευχθεί. Το ανάθεμα στον Ελευθέριο Βενιζέλο τον Δεκέμβριο του 1916 που οργάνωσαν οι επίστρατοι μαζί με τους προέδρους των επαγγελματικών σωματείων πραγματοποιήθηκε στο Πεδίο του Άρεως με την παρουσία του προκαθημένου της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος Θεόκλητου Μηνόπουλου, των μελών της Ιεράς Συνόδου της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος και του κλήρου, ρίχνοντας εν μέσω του εθνικού διχασμού του, τον λίθο του αναθέματος κατά του Ελευθερίου Βενιζέλου «του επιβουλευθέντος την βασιλείαν και την πατρίδα και καταδιώξαντος και φυλακίσαντος αρχιερείς». Όπως ήταν αναμενόμενο, η επιστροφή στην εξουσία του κόμματος των φιλελεύθερων συνοδεύτηκε αναγκαστικά με τις ανάλογες αλλαγές στο διοικητικό οργανισμό της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος. Η εμπλοκή του μητροπολίτη Αθηνών στο ανάθεμα κατά του Βενιζέλου καθιστούσε αδύνατη τη συνεργασία του ελληνικού κράτους με την Εκκλησία. Η αντικατάσταση του μητροπολίτη Αθηνών Θεοκλήτου Μηνόπουλου και των υπολοίπων ιεραρχών ήταν μονόδρομος. Ο πρωθυπουργός Ελευθέριος Βενιζέλος επέλεξε τον μητροπολίτη Κιτίου Μελέτιο Μεταξάκη, τον συμπατριώτη του και δυναμικότερο εκφραστή του Βενιζελισμού στην Κύπρο, για νέο μητροπολίτη Αθηνών. Ήταν μια δύσκολη απόφαση και η περισσότερο επιτυχημένη επιλογή του Βενιζέλου (29).

Μέσα σε αυτό το πολωμένο πολιτικά κλίμα ο γνωστός γλωσσολόγος και πανεπιστημιακός δάσκαλος Γεώργιος Χατζηδάκις αντέδρασε για όσες μεταβολές γίνονταν στον χώρο της εκπαίδευσης με κέντρο το γλωσσικό ζήτημα τον Απρίλιο του 1918 χωρίς να βρει ένθερμους υποστηρικτές μετά την ανοικτή υποστήριξη του πρωθυπουργού Βενιζέλου για τη χρήση της δημοτικής γλώσσας, σε αγόρευσή του στο κοινοβούλιο. Ο Γ. Χατζηδάκις υπήρξε εκτός από μεγάλος επιστήμονας και ένας εθνικός αγωνιστής. Σε ηλικία 18 ετών έλαβε μέρος στην επανάσταση της Κρήτης του 1866-1869, όπως και ως καθηγητής πανεπιστημίου σε ηλικία 49 ετών πολέμησε ως εθελοντής κατά των Οθωμανών. Η στάση του απέναντι στο γλωσσικό ζήτημα, που απασχολούσε με έντονο τρόπο την περίοδο εκείνη τόσο τους επιστημονικούς κύκλους όσο και τους πολιτικούς, οδήγησε τους αντιπάλους του να τον κατηγορήσουν ως αντεθνικό. Ο Γ. Χατζηδάκις ήταν ο πρώτος που εισήγαγε την γλωσσολογία ως ιδιαίτερο επιστημονικό κλάδο στην Ελλάδα, μετά από εμπεριστατωμένες σπουδές σε αυτήν στην γηραιά ήπειρο, στη δύση του 19ου αιώνα. Ο Γ. Χατζηδάκις αντιτάχθηκε σε όλους τους εκπροσώπους της αιολοδωρικής θεωρίας, οι οποίοι στηρίζονταν σε παρόμοιες απόψεις όπως αυτές του πατέρα του νεοελληνικού Διαφωτισμού Αδαμάντιου Κοραή, του Κωνσταντίνου Οικονόμου του εξ Οικονόμων κ.α. που πίστευαν πως η νεοελληνική δημώδης γλώσσα ανάγεται απευθείας στην αρχαία ελληνική (αιολική και δωρική διάλεκτο). Έτσι, απέδειξε σε αντίθεση με τις υπόλοιπες θεωρίες που βρίσκονταν την περίοδο εκείνη στο προσκήνιο της χώρας, πως η ομιλούμενη και η λόγια γραπτή γλώσσα συναποτελούν τη φυσική συνέχεια της βυζαντινής παράδοσης, που είναι η εξέλιξη της αλεξανδρινής κοινής (30).

Ο καθηγητής Γ. Χατζηδάκης δεν έμεινε με σταυρωμένα τα χέρια παρά τις δυσκολίες που θα αντιμετώπιζε και τις κυρώσεις εις βάρος του από την κυβέρνηση Ελευθέριου Βενιζέλου. Με την αρθρογραφία του στις ημερήσιες αντιβενιζελικές εφημερίδες της πρωτεύουσας προσπαθούσε να αφυπνίσει τους αντιπάλους του στρατοπέδου των δημοτικιστών. Στη συνέχεια, προσέγγισε τον προκαθήμενο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος Μελέτιο Μεταξάκη και ζήτησε την έμπρακτη συμπαράστασή του για το ζήτημα της γλώσσας. Στις 6 Ιουνίου 1919, στο μητροπολιτικό Μέγαρο της Αθήνας μια διαβούλευση επιστημόνων κατέληξε στην ίδρυση του Εκπαιδευτικού Συλλόγου, που ουσιαστικά ήταν το αντίπαλο δέος του Εκπαιδευτικού Ομίλου. Πρόεδρος του Εκπαιδευτικού Συλλόγου θα εκλεγεί ο καθηγητής Γ. Χατζηδάκις ο οποίος στο παρελθόν είχε ταχθεί υπέρ του βασιλέως Κωνσταντίνου Α’, κράτησε ήπια στάση και δεν ήταν απόλυτα ταυτισμένος με την φιλοβασιλική παράταξη. Η συμβολή του μητροπολίτου Αθηνών Μελετίου Μεταξάκη υπήρξε ιδιαίτερα σημαντική σε αυτή την περίπτωση, αφού ενίσχυσε με κάθε τρόπο και μέσο την συνολική δραστηριότητα του Εκπαιδευτικού Συλλόγου, δεχόμενος τη θέση του επίτιμου προέδρου κηρύσσοντας την έναρξη των εργασιών του συνεδρίου. Η δυναμική αυτή ενέργεια του μητροπολίτου Μελετίου Μεταξάκη τάραξε τα νερά και θεωρήθηκε από το κόμμα των Φιλελευθέρων μια καθαρά αντικυβερνητική ενέργεια. Ουδέποτε στο παρελθόν προκαθήμενος της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος δεν είχε έρθει ανοικτά σε ρήξη με το ελληνικό κράτος. Ο Εκπαιδευτικός Σύλλογος επιθυμούσε να εκφράσει το σύνολο των συντηρητικών δυνάμεων εντός και εκτός του βενιζελικού χώρου. Όχι μόνο οι φιλοβασιλικές αθηναϊκές ημερήσιες εφημερίδες αντιμετώπισαν με θετικό τρόπο αυτή την προσπάθεια, αλλά και οι φιλοκυβερνητικές εφημερίδες όπως η «Εστία» και ο «Ελεύθερος Τύπος», είδαν στην αρχή με καλό μάτι το συνέδριο της μητροπόλεως Αθηνών. Η κυβέρνηση και το κόμμα των Φιλελευθέρων με σύμμαχό τους τις ημερήσιες εφημερίδες που ανήκαν στον πολιτικό τους χώρο αντέδρασαν δυναμικά και άμεσα (31).

Το κόμμα δεν μπορούσε να συγχωρέσει την στάση του μητροπολίτου Αθηνών Μελετίου ο οποίος ήταν η προσωπική επιλογή του πρωθυπουργού. Ο υπουργός Δημήτριος Δίγκας φοβούμενος την εμπλοκή του μητροπολίτου Αθηνών με τους υποστηρικτές της καθαρεύουσας, οι οποίοι στη συντριπτική τους πλειονότητα ήταν αντιβενιζελικοί, αναλαμβάνει δράση με στόχο να τεκμηριώσει την αντίθεσή του για την ανάμειξη στο ζήτημα αυτό της ελλαδικής Εκκλησίας, προβαίνει σε δηλώσεις στον Τύπο για να επιβεβαιώσει πως η εκπαιδευτική μεταρρύθμιση περιορίζεται μόνο στο γλωσσικό και όχι στο περιεχόμενο της θρησκευτικής ηθικής και εθνικής αγωγής της νεολαίας. Μετά την καταδίκη από την πλευρά της κυβερνήσεως της συμμετοχής της Εκκλησίας και συντηρητικών βενιζελικών που ήταν παρόντες στο μητροπολιτικό μέγαρο όπως εκείνη του Ευστράτιου Κουλουμβάκη, νομάρχη Αττικοβοιωτίας και στελέχους του κόμματος των φιλελευθέρων και του μητροπολίτη Μελετίου θα αναγκαστούν να αποστασιοποιηθούν, επιβεβαιώνοντας την ταύτισή τους με την κυβέρνηση Ελ. Βενιζέλου. Όπως γράφει ημερήσια εφημερίδα της εποχής ο Αθηνών Μελέτιος δήλωσε: «Εάν δεν εγνώριζον ως ακραιφνώς Φιλελεύθερα τα πρόσωπα […] και αν δεν ήμην βέβαιος ότι πάντες οι συνελθόντες είναι φίλοι του καθεστώτος, ούτε την αίθουσαν θα ήνοιγον εις την Συνέλευσιν, ούτε των συσκέψεων αυτής θα μετείχον» (32).

Η φιλοβενιζελική πλευρά και ο προσκυνημένος σε αυτήν Τύπος δημοσίευσε άρθρα για το ζήτημα ώστε να μην αφήσει ίχνος υποψίας για την αλλαγή στάσης της Εκκλησίας και του προκαθημένου της Μελετίου Μεταξάκη ότι δεν ταυτιζόταν πλέον με το βενιζελικό στρατόπεδο. Χαρακτηριστικό του κλίματος είναι τα δημοσιεύματα των ημερησίων εντύπων όπως αποτυπώνονταν στις στήλες τους.

«Ανακοινώσεις του υπουργού της Παιδείας Περί του γλωσσικού

Σχετικώς με το ανακινηθέν γλωσσικόν ζήτημα, ο υπουργός της Παιδείας, προς ον απετάθημεν, μας ανεκοίνωσε τα εξής: “Βεβαίως η Κυβερνητική αντίληψις είνε ότι άτομα ή ομαδικαί οργανώσεις δύνανται να έχωσι διάφορον γνώμην επί της εκπαιδευτικής πολιτικής της Κυβερνήσεως όπως και επί της καθ’ όλου πολιτικής αυτής. Αλλ’ από του σημείου τούτου μέχρι και του να αναμιγνύωνται εις την εκπαιδευτική πολιτικήν της Κυβερνήσεως πρόσωπα κατέχοντα δημοσίας θέσεις, η απόστασις είνε μεγάλη. Διά τούτο εξητάσθη υπό τον Σεβ. Μητροπολίτην, ο οποίος ως εκ της θέσεώς του των υπηρεσιακών σχέσεών του με το Υπουργείον δύναται να έχη γνώμην επί των εκπαιδευτικών ζητημάτων, εφ’ όσον μάλιστα πρόκειται περί θρησκευτικών τοιούτων, εάν πράγματι συνέβησαν εν τω Μητροπολιτικώ μεγάρω όσα δεν εξηγγέλθησαν διά του Τύπου, δεδομένου εκτός των άλλων ότι η ανάμιξις θρησκευτικών αρχηγών εις τοιαύτα ζητήματα ανέκαθεν έδωσεν αφορμάς εις σοβαράς παρεξηγήσεις και ταραχάς.

Περιεργοτέρα, όμως, προσέθηκεν ο κ. Υπουργός, είνε η ανάμιξις του κ. Νομάρχου Αττικής εις το ζήτημα και αι γνώμαι του επ’ αυτού, αν πράγματι απεδόθησαν αύται υπό του Τύπου ακριβώς. Διά τούτο εζητήθη και από τον κ. Νομάρχην να βεβαιώση αν όσα ανεγράφησαν περί αυτού είνε αληθινά”.

Δεδομένου ότι η εκπαιδευτική πολιτική της Κυβερνήσεως είνε γνωστή, πιστοποιείται δε και εκ των ανωτέρω ανακοινώσεων του κ. Δίγκα, αναμένονται τα κατάλληλα μέτρα κατά της παρατηρηθείσης κατά τας τελευταίας ημέρας κινήσεως εκπαιδευτικών συγκεντρώσεων διά το γλωσσικόν ζήτημα (33).

Αναταράσσει πλέον πάλιν τους φιλολογικούς κύκλους τους μαθητικούς όχι ακόμη ευτυχώς! – το πολύκροτον γλωσσικόν ζήτημα, το οποίον έφθασε μέχρι της Εθνοσυνελεύσεως προ ολίγων ετών χωρίς να… υπάρχη και ο μακαρίτης Δηλιγιάννης εις την ζωήν, διά να συνδέση το ζήτημα αυτό με τους δακτύλους, τους υποσκάπτοντας τα Εθνικά ιδεώδη, με τον Πανσλαυϊσμόν και με τους κινδυνεύοντας… θεσμούς!

Αφορμήν εις την ανακίνησιν του ζητήματος το οποίον, σημειωτέον, δεν παύει υποβόσκον πάντοτε και όπερ ομοιάζει προς ηφαίστειον παθαίνον κατά περιόδους εκρήξεις, έδωσε, κατά τους ισχυρισμούς τουλάχιστον του κ. Χατζηδάκι, ομιλήσαντος εις την προχθεσινήν συγκέντρωσιν του Μητροπολιτικού μεγάρου, “περί του κινδύνου, ον διατρέχει η πάτριος γλώσσα”, η εισαγωγή βιβλίων εγκεκριμένων εις τα Δημοτικά σχολεία, όπως “Τα Ψηλά Βουνά” του γνωστού λογίου και λογογράφου μας.

Η συγκέντρωσις εγένετο εις το Μητροπολιτικόν μέγαρον, κατόπιν προσκλήσεως την οποίαν είχαν υπογράψει παραδόξως, έξω των γνωστών τύπων γλωσσαμυντόρων άνδρες, οίτινες υπήρξαν εκ των καταπολεμησάντων τους υπερσχολαστικίζοντας γλωσσαμύντορας, τους ευρισκομένους εις τους αντίποδας των υπερμαλλιαρών ψυχαριστών, με τον αείμνηστον Μιστριώτην επί κεφαλής. Ούτε είδομεν την πρόσκλησιν φέρουσαν τας υπογραφάς του Χατζηδάκι, του Μενάρδου, του Σκιά, των γνωστών καθηγητών της Φιλοσοφικής Σχολής, καθώς και του καθηγητού του Διοικητικού Δικαίου κ. Αγγελοπούλου. Εις την σύσκεψιν μετέσχον επιστήμονες, δικηγόροι, καθηγηταί, βουλευταί και άλλοι, με θέμα το ζήτημα των εκπαιδευτικών πραγμάτων του Κράτους, άτινα “υπολείπονται πολύ του επιθυμητού”, κατά την σχετικήν περικοπήν της προσκλήσεως. Ο Σεβ. Μητροπολίτης ωμίλησε πρώτος περί της καθυστερήσεως της Εκπαιδεύσεως και της ανάγκης ιδρύσεως συλλόγου, όστις να έλθη αρωγός της Κυβερνήσεως εις την διόρθωσιν των μεγάλων ελλείψεων της Εκπαιδεύσεως. Έλαβε κατόπιν τον λόγον ο Χατζη- δάκις, όστις δεν ήργησε να καταστήση πρόδηλον, ότι κυρίως θα ενδιέφερε τους συνελθόντας το ζήτημα της γλώσσης. Αλλ’ κ. Περικλής Καραπάνος δεν αφήκεν αναπάντητον τον προαγορεύσαντα. Διεμαρτυρήθη ζωηρώς διά τον υποκρυπτόμενον σκοπόν της συγκεντρώσεως, και ετόνισεν ότι αυτός, ων εκ των ιδρυτών του “Εκπαιδευτικού Ομίλου”, δεν δύναται να συμμετάσχη εις εργασίαν, στρεφομένην κατά της εκπαιδευτικής αναγεννήσεως, ακόμη δε και κατά του προγράμματος του Φιλελευθέρου Κόμματος, επί του προκειμένου. Η ρητή και απροκάλυπτος αυτή δήλωσις του κ. Καραπάνου, ομιλούντος την φωνήν της ειλικρινείας, προεκάλεσεν αντιδιαμαρτυρίας τινων των παρισταμένων, οι οποίοι ισχυρίσθησαν, ότι δεν πρόκειται περί πολεμικής και επιθέσεως κατά του Υπουργείου της Παιδείας, αλλά μάλλον περί αμύνης κατά του γλωσσικού κινδύνου. Και επομένως θα έχωμεν νέους γλωσσαμύντορας και νέους γλωσσικούς.

Ήτο καιρός όμως να γίνη και αυτό! Ο καιρός της Εθνοσυνελεύσεως δεν είνε μακράν. Τι διάβολο, να μην υπάρχη γλωσσικόν ζήτημα εις μίαν Συντακτικήν Εθνοσυνέλευσιν;

Η σύσκεψις έληξε με μίαν γραπτήν διαμαρτυρίαν, αποσταλείσαν υπό του Διευθυντού του Πολυτεχνείου κ. Γκίνη, αποκρούοντος την συμμετοχήν του εις σύσκεψιν αφορώσαν ζητήματα εκπαιδευτικά και γλωσσικά, εις ην δεν έχει θέσιν ο κλήρος, η ανάμιξις του οποίου έχει καταδειχθή ότι συντελεί μόνο εις δημιουργίαν “δεισιδαιμονίας και αδικαιολογήτου μεσαιωνικού φανατισμού” και με την ίδρυσιν “Εκπαιδευτικής Ενώσεως”, ης εψηφίσθη και το καταστατικόν. Τοιουτοτρόπως θα έχωμεν εις το μέλλον τον “Εκπαιδευτικόν Όμιλον” και την “Εκπαιδευτικήν Ένωσιν”.

Εν τω μεταξύ, εννοείται, η γλώσσα μας, ξένη από κάθε περιορισμόν, θα εξακολουθήση την προοδευτικήν εξέλιξίν της. Και ίσως, ή μάλλον πιθανώτατα, οι δύο Σύλλογοι να… τριτώσουν!

Ε.Ν.ΜΗ» (34).

Με σκωπτικό ύφος εφημερίδα φιλοβενιζελική σχολιάζει την εμπλοκή του Αθηνών Μελετίου στο γλωσσικό ζήτημα, ο οποίος αφού είχε δώσει λύση σε όλα τα προβλήματα τα εκκλησιαστικά «μη έχων άλλο τι σπουδαιότερον να κάμη εξέτεινε την ευεργετικήν του δράσιν και εις την γλώσσαν των Ελλήνων, την οποίαν θέλει καθαράν όπως είνε καθαραί και χείρες όλων των λειτουργών του Υψίστου». Η εφημερίδα συνεχίζοντας τις υποδείξεις της στον μητροπολίτη αναφέρεται σε παλαιότερη δήλωση του Βενιζέλου στη Θεσσαλονίκη ότι, εάν η επανάσταση δεν είχε καμία άλλη επιτυχία, θα ήταν δικαιολογημένη γιατί εισήγαγε στα σχολεία τη δημοτική γλώσσα. Το έντυπο υπενθυμίζει στους αναγνώστες του ότι οι άνθρωποι αυτοί που έλαβαν μέρος στο συνέδριο ήταν όλοι επιλογή του Βενιζέλου, οι οποίοι χωρίς αυτόν θα ήταν ασήμαντοι. Στη συνέχεια προτρέπει τον αντιπρόεδρο της κυβερνήσεως Ρέπουλη “ότι οφείλει να είπη εις τους νέους αυτούς συνοδικούς παπάδες και λαϊκούς” και αποσυναγωγούς υμάς ποιήσω» (35).

Ο αρμόδιος υπουργός Δ. Δίγκας ενημέρωσε το υπουργικό συμβούλιο για τις εξελίξεις γύρω από τις αντιδράσεις στο γλωσσικό και την αποστολή σχετικού εγγράφου προς τον μητροπολίτη Αθηνών διατάζοντας ταυτόχρονα ανακρίσεις κατά των αναμιχθέντων λειτουργιών της εκπαίδευσης (36). Το περιεχόμενο του εγγράφου προς τον μητροπολίτη Μελέτιο δημοσιεύει άλλη εφημερίδα και τον καλούσε «να περιορισθή εις τα φιλανθρωπικά του έργα, και να μην επεμβαίνη εις έργα επιστημονικόν αγώνα. Ούτω τίθενται σαφώς τα όρια της μητροπολιτικής δράσεως. Το υπουργείο αναμένει ήδη την απάντηση του μητροπολίτου» (37).

Η απάντηση του Μελετίου Μεταξάκη στο υπουργείο συνετέλεσε ώστε να πέσουν οι τόνοι μεταξύ Πολιτείας και Εκκλησίας και αυτό άρχισε να αντικατοπτρίζεται στις ημερήσιες φιλοβενιζελικές εφημερίδες.

«Η απάντησις του Σεβασμιώτατου Μητροπολίτου εις το υπουργείον της Παιδείας

Ως πληροφορούμεθα ο Σ. Μητροπολίτης κ. Μελέτιος απήντησεν ήδη προς την γνωστήν έγγραφον σύστασιν του υπουργείου της Παιδείας περί μη αναμίξεώς του εις αλλότρια της δικαιοδοσίας του καθήκοντα. Διά της απαντήσεώς του ο Σεβασμιώτατος επεξηγεί ότι εν αγνοία του σκοπού των εφιλοξένησεν εν τω Μητροπολιτικώ μεγάρω τους γλωσσαμύντορας, δηλοί δε ότι εις το μέλλον δεν θ’ αναμιχθή εις άλλα ζητήματα εκτός των καθαρώς εκκλησιαστικών» (38).

«Θεωρείται λήξαν.

Εσφαλμένως πως διευτυπώθη η απάντησις του Σ. Μητροπολίτου εις το γνωστόν έγγραφον του υπουργείου διά την Γλώσσαν. Πάντως το ζήτημα θεωρείται λήξαν αφ’ ότου συνεννοήθη επ’ αυτού ο κ. Υπουργός μετά του Σεβασμιωτάτου» (39).

Η ήττα του Ελευθερίου Βενιζέλου στις εκλογές της 1ης Νοεμβρίου 1920 μετέβαλε την πορεία του εκπαιδευτικού συστήματος για ακόμα μια φορά. Την εξέλιξη αυτή ακολούθησε η παραίτηση των Δημητρίου Γληνού, Αλέξανδρου Δελμούζου και του Μ. Τριανταφυλλίδη. Η κυβέρνηση του Δ. Ράλλη συγκρότησε «Επιτροπεία» για τη μελέτη της κατάστασης, στα σχολεία, με έμφαση το ζήτημα της διδασκαλίας της δημοτικής στα δημοτικά σχολεία. Η Επιτροπεία κατέληξε στο συμπέρασμα ότι έπρεπε να ακυρωθούν οι νόμοι για την εισαγωγή της δημοτικής γλώσσας των σχολικών εγχειριδίων. Στη συνέχεια πρότεινε τη συγγραφή καινούργιων βιβλίων και ενόσω αναμενόταν να διανεμηθούν αυτά στις σχολικές αίθουσες, οι εκπαιδευτικοί θα χρησιμοποιούσαν τα αντίστοιχα σχολικά που υπήρχαν πριν από το έτος 1917. Η Επιτροπεία ζήτησε την ποινική δίωξη των υπευθύνων για την υποβάθμιση της γλώσσας (40).

Οι πολιτικές εξελίξεις στη διάρκεια του μεσοπολέμου στην Ελλάδα, η τριπλή κατοχή της χώρας από τα ξένα στρατεύματα κατά τη διάρκεια του Β’ Παγκοσμίου Πολέμου και τα τραγικά γεγονότα που ακολούθησαν, στην περίοδο 1946-1949 δεν άφησαν το περιθώριο για την αναψηλάφηση του γλωσσικού ζητήματος. Το 1932 η κυβέρνηση Βενιζέλου προσπαθεί να ολοκληρώσει το έργο της που είχε από το 1917 αναλάβει και ζητάει από τον Μανόλη Τριανταφυλλίδη τη σύνταξη γραμματικής στη δημοτική γλώσσα. Η πτώση της τελευταίας κυβέρνησης Βενιζέλου σταμάτησε αυτή την προσπάθεια. Η περίοδος της διακυβέρνησης της χώρας από τον Ιωάννη Μεταξά χαρακτηρίζεται από μια ευνοϊκή διάθεση απέναντι στη δημοτική γλώσσα. Η Ευαγγελία Καλεράντε γράφει: «Μια αρχική εκτίμηση είναι ότι δεν πραγματοποιείται η τομή που θα περίμενε κανείς με βάση τις θέσεις του ίδιου του Μεταξά στο θέμα της γλώσσας, που είχε διατυπώσει θέσεις υπέρ της δημοτικής ως γλωσσικής αποσπασματικής επιλογής, διαφοροποιούμενος ταυτόχρονα από τους συντηρητικούς, αλλά και από τις θέσεις των προοδευτικών για τον εκπαιδευτικό δημοτικισμό» (41).

Η Εκκλησία της Ελλάδος εκείνη την περίοδο, όπως και τον 19ο αιώνα για το μάθημα των Θρησκευτικών, είναι επιφορτισμένη με την έγκριση των διδακτικών εγχειριδίων στην πρωτοβάθμια και δευτεροβάθμια εκπαίδευση, σε ό,τι αφορούσε στο περιεχόμενό τους. Οι υποψήφιοι συγγραφείς έπρεπε μόλις εκδίδονταν οι νέες προκηρύξεις για τη συγγραφή νέων σχολικών βιβλίων να υποβάλουν αίτηση προς το αρμόδιο υπουργείο, το οποίο ανάθετε σε επιτροπές την αξιολόγησή τους για να λάβουν την έγκριση η οποία θα αναγραφόταν μέσα σε αυτά, ώστε να μπορούν νόμιμα να διανεμηθούν στις σχολικές αίθουσες. Για το μάθημα των θρησκευτικών, εκτός από την άδεια του αρμόδιου υπουργείου, θα έπρεπε να έχουν και την έγκριση της Ιεράς Συνόδου της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος, με την αναγραφή της στο συγκεκριμένο βιβλίο. Η εποπτεία του ελληνικού κράτους η οποία διαρκούσε έναν αιώνα για τον τρόπο συγγραφής, κρίσεως και διαθέσεως στην αγορά των σχολικών βιβλίων τερματίστηκε με την έκδοση του Αναγκαστικού Νόμου 952/1937. «Περί ιδρύσεως Οργανισμού Εκδόσεως Σχολικών Βιβλίων υπό την εποπτεία του αρμόδιου υπουργείου». Τα σχολικά βιβλία διακρίνονται σε διδακτικά και βοηθητικά, στα οποία συμπεριλαμβάνονταν και εκείνα του μαθήματος των θρησκευτικών. Στο δημοτικό σχολείο διδακτικά βιβλία ήταν το αναγνωστικό και η γραμματική και για τη δευτεροβάθμια εκπαίδευση όλα τα βιβλία όλων των τάξεων. Ανάμεσα στα βοηθητικά βιβλία του δημοτικού για την Ε’ και ΣΤ’ τάξη είναι και εκείνα του μαθήματος των θρησκευτικών και δεν υπάρχει περιορισμός στον αριθμό των εγκεκριμένων βιβλίων ούτε από το υπουργείο και την Ιερά Σύνοδο της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος (42).

Η απελευθέρωση της Ελλάδος από τα στρατεύματα της τριπλής κατοχής τον Οκτώβριο του 1944 άνοιξε το δρόμο για την επιστροφή της νόμιμης κυβέρνησης στην πρωτεύουσα. Μαζί με τον Άγγλο στρατηγό Scobie, αποβιβάζεται στις 18 του μηνός στο λιμάνι του Πειραιά. Στις 23 Οκτωβρίου ορκίζεται πρωθυπουργός ο Γεώργιος Παπανδρέου, ο οποίος διέταξε των αποστράτευση των αντάρτικων ομάδων, ενώ η κλάση του 1936 έπρεπε να σχηματίσει την «προσωρινήν εθνοφυλακήν». Μετά την απόφαση εκ μέρους των μελών του ΚΚΕ και του ΕΑΜ να ζητήσουν τη διάλυση ταυτόχρονα με τις ομάδες των ανταρτών του Ιερού Λόχου μαζί με την ορεινή ταξιαρχία και να γίνει αποστράτευση των χωροφυλάκων. Με την απόρριψη των συγκεκριμένων αιτημάτων τους, οι έξι υπουργοί της Αριστεράς αποφάσισαν να αποχωρήσουν από το κυβερνητικό σχήμα. Στις 3-12-1944 στο συλλαλητήριο που ακολούθησε στο Σύνταγμα άρχισαν οι συγκρούσεις που οδήγησαν στα Δεκεμβριανά (43).

Εκείνη την περίοδο αρχιεπίσκοπος Αθηνών ήταν ο Δαμασκηνός Παπανδρέου. Μετά τον θάνατο του αρχιεπισκόπου Αθηνών Χρυσόστομου Παπαδόπουλου προκύπτει για δεύτερη φορά αρχιεπισκοπικό ζήτημα. Η επιθυμία του μητροπολίτη Τραπεζούντος Χρυσάνθου για τον αρχιεπισκοπικό θρόνο της Αθήνας έφερε στο προσκήνιο την αντιπαράθεση μεταξύ των δύο ομάδων που σχηματίσθηκαν την περίοδο του εθνικού διχασμού, μεταξύ του Μελετίου Μεταξάκη και Θεόκλητου Μηνόπουλου. Συνυποψήφιοι για τον αρχιεπισκοπικό θώκο ήταν ο μητροπολίτης Κορινθίας Δαμασκηνός Παπανδρέου, ο οποίος προερχόταν από τους λεγόμενους «Πλαστηρογέννητους αρχιερείς». Ο Κορινθίας Δαμασκηνός Παπανδρέου αναδείχθηκε μετά από τρεις αλλεπάλληλες συνεδριάσεις μέσα στην ίδια μέρα, στις 5-11-1938, νέος προκαθήμενος της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος. Ο αντιπρόεδρος της Ιεράς Συνόδου του παρέδωσε σε επίσημη τελετή τη διοίκηση της Ιεράς Αρχιεπισκοπής Αθηνών. Το καθεστώς της 4ης Αυγούστου κατάφερε ύστερα από μια σειρά μεθοδεύσεων να ακυρώσει την εκλογή του και να προωθήσει τον Χρύσανθο Τραπεζούντος στον αρχιεπισκοπικό θρόνο. Ο Δαμασκηνός Παπανδρέου εκτοπίστηκε στην ιερά μονή Φανερωμένης στη Σαλαμίνα. Μετά την εισβολή του γερμανικού στρατού στην Αθήνα και τη συνθηκολόγηση του στρατηγού Γ. Τσολάκογλου, ο βασιλιάς και η κυβέρνηση έφυγαν για τη Μέση Ανατολή, χωρίς ο Αθηνών Χρύσανθος να τους ακολουθήσει. Στη συνέχεια αρνήθηκε να ορκίσει τη δωσιλογική κυβέρνησή του Γ. Τσολάκογλου, να παρευρεθεί στην παράδοση της πρωτεύουσας και να τελέσει δοξολογία στο μητροπολιτικό ναό Αθηνών. Οι μεθοδεύσεις που τον οδήγησαν στον αρχιεπισκοπικό θώκο επανήλθαν στο προσκήνιο από τη δοσιλογική κυβέρνηση, που γνώριζε τις παραβιάσεις του εκκλησιαστικού και κανονικού δικαίου. Τότε συγκάλεσε, στις 2-7-1941 μείζονα Σύνοδο, για να ακυρωθεί η εκλογή του Αθηνών Χρυσάνθου και να ανοίξει ο δρόμος της επιστροφής του Δαμασκηνού Παπανδρέου. Στις 25 Δεκεμβρίου 1944 έφθασε στην Ελλάδα ο Winston Churchill στις 25-11-1944, ο οποίος ενημέρωσε τον αρχιεπίσκοπο Αθηνών Δαμασκηνό πως η επιθυμία του βασιλιά και των συμμάχων ήταν να αναλάβει αντιβασιλέας. Στις 28-12-1944, στο υπουργείο Εξωτερικών γίνεται η ορκωμοσία του ως αντιβασιλέα και παρέμεινε μέχρι τις 28-9-1946, οπότε επανήλθε στον θρόνο ο βασιλιάς Γεώργιος Β’ (44).

Ο πρωθυπουργός Γ. Παπανδρέου διορίζει γενικό διευθυντή του υπουργείου Παιδείας του Ευάγγελο Π. Παπανούτσο. Στη θέση του γενικού διευθυντή του υπουργείου παρέμεινε από τον Νοέμβριο του 1944 ως τον Μάιο του 1946. Στη δύσκολη αυτή περίοδο που ολόκληρη η χώρα είχε διαλυθεί από τον πόλεμο και την τριπλή κατοχή το εκπαιδευτικό σύστημα ήταν αποδιοργανωμένο, ενώ μέσα σε 15 μήνες είχαν αλλάξει 6 υπουργοί παιδείας. Ένας από αυτούς τους υπουργούς ήταν ο καθηγητής της Βυζαντινής Ιστορίας στο Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών Κ. Άμαντος ο οποίος είχε εκδιωχθεί από το πανεπιστήμιο από το καθεστώς της 4ης Αυγούστου. Τον Φεβρουάριο του 1945 ο Κ. Άμαντος με εισήγηση του Ε.Π. Παπανούτσου προώθησε στο υπουργικό συμβούλιο ένα νόμο για την καθιέρωση της δημοτικής γλώσσας. Ο Φαν. Βώρος γράφει: «Το κείμενο που παραθέτει ο Παπανούτσος στα Απομνημονεύματά του (σ. 52-53):

Άρθρο 1: Η Δημοτική, η νεοελληνική Κοινή, είναι γλώσσα εθνική και αναγνωρίζεται η βασική της σημασία διά την Ελληνικήν Παιδείαν.

Άρθρο 2: Εις την λαϊκήν εκπαίδευσιν η Δημοτική γλώσσα ορίζεται ως γλώσσα των διδακτικών βιβλίων και της διδασκαλίας…

Άρθρο 3: Η Δημοτική γλώσσα, μετά της Νεοελληνικής Λογοτεχνίας, λαμβάνει βασικήν θέσιν εις το πρόγραμμα μαθημάτων των σχολείων της Μέσης Εκπαιδεύσεως ως και των Πανεπιστημιακών Σχολών, αι οποίαι καταρτίζουν τους καθηγητάς της Μέσης Εκπαιδεύσεως». Αλλά ο αρχιεπίσκοπος «Δαμασκηνός. αρνήθηκε να υπογράψει τον αναγκαστικό νόμο και έτσι η πρώτη αυτή απόπειρα για την επίσημη αναγνώριση της Δημοτικής απέτυχε» (45).

Υποσημειώσεις

(1) Έλλη Σκοπετέα, «Αρχαία, Καθομιλουμένη και Καθαρεύουσα Ελληνική Γλώσσα», στο Α.Φ. Χριστίδης (επιμ.) Ιστορία της Ελληνικής Γλώσσας. Από τις αρχές έως την ύστερη αρχαιότητα, Ινστιτούτο Νεοελληνικών Σπουδών, Αθήνα, σελ. 958-960.

(2) Αντώνης Σατραζάνης, «Η γλώσσα της λογοτεχνίας του 19ου αιώνα, διαμέσου μίας γλωσσικής διαμάχης. Η περίπτωση του Γιάννη Ψυχάρη» στην Επιστημονική Επετηρίδα Παιδαγωγικό Τμήμα Δημοτικής Εκπαίδευσης, Παιδαγωγικό Τμήμα Νηπιαγωγών, Γενικό Τμήμα, Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλίας, τόμ. 1ος, Βόλος 1999, σελ. 229-235.

(3) Πασχάλης Κιτρομηλίδης, «Νοερές κοινότητες και οι απαρχές του εθνικού ζητήματος στα Βαλκάνια», στο Θάνος Βερέμης, Εθνική ταυτότητα και εθνικισμός στη νεότερη Ελλάδα, Μορφωτικό Ίδρυμα Εθνικής Τραπέζης, Αθήνα 2012(4), σελ. 53-131.

(4) Δημήτρης Διαμαντής, Τα σχολικά προγράμματα στην πρωτοβάθμια εκπαίδευση και η πολιτική ιδεολογία (1830-1920), Συμβολή στην ιστορία της νεοελληνικής εκπαίδευσης, εκδόσεις Γρηγόρη, Αθήνα 2006, σελ. 249-249.

(5) Ανδρέας Νανάκης, (αρχιμ. νυν μητροπολίτης), Εκκλησία Γένος, Ελληνισμός, εκδ. «Τέρτιος», Κατερίνη 1193, σελ. 67-71.

(6) Ευάγγελος Κωφός, Η Ελλάδα και το ανατολικό ζήτημα, Εκδοτική Αθηνών, Αθήνα 2001, σελ. 29-31.

(7) Αθανάσιος Σωτ. Καρυάμης (πρωτ.), Από τον εθνικό στον εκκλησιαστικό δι-

χασμό: τα προηγηθέντα του αναθέματος στον Βενιζέλο (1916) και τα μετέπειτα επί αναμίξει εις κοσμικάς φροντίδας, εκδόσεις Ηρόδοτος, Αθήνα 2021, σελ. 114-117.

(8) Χρήστος Βούλγαρης, Εισαγωγή εις την Καινήν Διαθήκην, τόμος Β’, χ.τ., χ.ε., 2005, σελ. 1361-1365.

(9) Γεώργιος Μεταλληνός (πρωτ.), Το ζήτημα της μεταφράσεως της Αγίας Γραφής εις την νεοελληνικήν κατά τον ΙΘ’ αι. (επί τη βάσει ιδία των αρχείων της ΒΤΒ8, CMS, LMS, του κ. Τυπάλδου-Ιακωβάτου και του Θ. Φαρμακίδου), εκδ. Αρμός, Αθήνα 2004, σελ. 292 (διδακτορική διατριβή).

(10) Σταύρος Γιαγκαζογλου, «Μία ποιητική “Βίβλος” στην καρδιά της Αγίας Γραφής: Με αφορμή την έκδοση του Ψαλτηρίου της Ελληνικής Βιβλικής Εταιρίας», στο Κώστας Γ. Τσικνάκης, Μαρία Σικ (επιμ.), Βιβλικές μεταφράσεις, ιστορία και πράξη. Επετειακός επιστημονικός τόμος για τα διακόσια χρόνια της Ελληνικής Βιβλικής Εταιρίας, Ελληνική Βιβλική Εταιρία, Αθήνα 2021, σελ. 109-129.

(11) Απόστολος Βακαλόπουλος, Νέα ελληνική ιστορία 1204-1985, εκδόσεις Βάνιας, Θεσσαλονίκη 2005 (23), σελ. 318-323.

(12) Χρήστος Καρβούνης, Το κατά Ματθαίου Ευαγγέλιο από τον Αλ. Πάλλη. Ζητήματα μετάφρασης της Αγίας Γραφής, Πανεπιστημιακές εκδόσεις Κρήτης, Ηράκλειο 2022, σελ. 96-97.

(13) Ελένη Κακουλίδη, Για τη μετάφραση της Καινής Διαθήκης: ιστορία, κριτική απόψεις, βιβλιογραφία, Θεσσαλονίκη 1970, χ.ε. (εκτός εμπορίου), σελ. 20-21.

(14) Εμμανουήλ Κωνσταντινίδη, Τα Ευαγγελικά: το πρόβλημα της μεταφράσεως της Αγ. Γραφής εις την νεοελληνικήν και τα αιματηρά γεγονότα του 1901, εν Αθήναις 1975, χ.ε., σελ. 108-116.

(15) Αθανάσιος Σωτ. Καρυάμης (πρωτ.), Εκφάνσεις πολιτειοκρατίας: Οι ωμές επεμβάσεις της πολιτείας στις εκλογές των προκαθημένων της Εκκλησίας της Ελλάδος (1833-1974), εκδόσεις Ηρόδοτος, Αθήνα 2020, σελ. 107.

(16) Αριστείδης Πανώτης, Το Συνοδικόν: ήτοι Επίτομος ιστορία της εν Ελλάδι Εκκλησίας κυρίως ως θυγατρός του Οικουμενικού Πατριαρχείου, τόμ. Β’, 1850-1922, εκδοθέν Τύποις Επταλόφου, Αθήνησι 2009, σελ. 255-257.

(17) Παυσανίας Κουτλεμάνης, Εισαγωγή στην κριτική του κειμένου της Καινής Διαθήκης, Θεσσαλονίκη 1995, χ.ε. σελ. 133-135.

(18) Δέσποινα Μιχάλαγα, «Ευαγγελικά: “Η βεβήλωσις του Ιερού Ευαγγελίου” πρόξενος των αιματηρών γεγονότων του 1901», στο Κώστας Γ. Τσικνάκης, Μαρία Σικ, Βιβλικές μεταφράσεις ιστορία και πράξη, επετειακός επιστημονικός τόμος για τα διακόσια χρόνια της Ελληνικής Βιβλικής Εταιρείας, Ελληνική Βιβλική Εταιρία, Αθήνα 2021, σελ. 147-174.

(19) Αριστείδης Πανώτης, Το Συνοδικόν…, ό.π., σελ. 258-259.

(20) Θεοκλήτος Στράγκας (αρχιμ.), Εκκλησίας Ελλάδος, Ιστορία εκ πηγών αψευδών (1817-1967), τόμ. Α’ Αθήναι 1969 χ.ε., σελ. 522-525.

(21) Ε. Κωνσταντινίδης, ό.π., σελ. 144-148.

(22) Άντα Διάλλα, «Ευαγγελικά και πανσλαβισμός: ο παράδοξος συσχετισμός», στο Ευαγγελικά (1901) – Ορεστιακά (1903) Νεώτερες πιέσεις και κοινωνικές αντιστάσεις (31 Οκτωβρίου & 1 Νοεμβρίου 2003), Εταιρεία Σπουδών νεοελληνικού Πολιτισμού και Γενικής Παιδείας, σελ. 43-61.

(23) Άλκηστις Βερέβη, «Ευαγγελικά και Ορεστιακά. Το χρονικό των γεγονότων» στο Ευαγγελικά (1901) – Ορεστιακά (1903). Νεωτερικές πιέσεις και κοινωνικές αντιστάσεις. (31 Οκτωβρίου & 1 Νοεμβρίου 2003), Εταιρεία Σπουδών Νεοελληνικού Πολιτισμού και Γενικής Παιδείας, σελ. 27-42.

(24) Αθανάσιος Σωτ. Καρυάμης (πρωτ.), Τα δημοσιεύματα των φιλοβενιζελικών αθηναϊκών ημερησίων εφημερίδων για τον Αθηνών Μελέτιο Μεταξάκη (1918-1920), εκδόσεις Ηρόδοτος, Αθήνα 2018, σελ. 465-467).

(25) Γιώργος Αναστασιάδης – Ευάγγελος Χεκίμογλου, Δημήτριος Γ. Δίγκας, (18761974). Η ζωή και το έργο του πρώτου μακεδόνα υπουργού, University Studio Press, Θεσσαλονίκη 2002, σελ. 153.

(26) Νικόλαος Τσίρος, Η νομοθεσία του Ελευθερίου Βενιζέλου κατά την περίοδο 1911-1920 στα πλαίσια της μεταρρυθμιστικής του πολιτικής και στα κοινωνικοπο- λιτικά δεδομένα της εποχής, εκδ. Παπαζήση, Αθήνα 2013, σελ. 143-144.

(27) Χάρης Αθανασιάδης, Τα αποσυρθέντα βιβλία: «Έθνος και σχολική ιστορία στην Ελλάδα 1858-2008», εκδ. Αλεξάνδρεια, Αθήνα 2015, σελ. 188-195.

(28) Αθανάσιος Σωτ. Καρυάμης (πρωτ.), Τα δημοσιεύματα, ό.π., σελ. 143.

(29) Αθανάσιος Σωτ. Καρυάμης (πρωτ.), Σημεία τριβής στις σχέσεις Εκκλησίας και Πολιτείας: η περίπτωση του πρώην Αθηνών Ιακώβου Γ’ Βαβανάτσου (18951984) και η στάση του εγχώριου Τύπου, εκδ. Ηρόδοτος, Αθήνα 2022, σελ. 85-86.